When it comes to organic foods, everyone seems to benefit. Consumer demand for organically produced goods continues to show double-digit growth, which results in market incentives for U.S. farmers across a broad range of products, reports the Economic Research Service, a USDA agency.

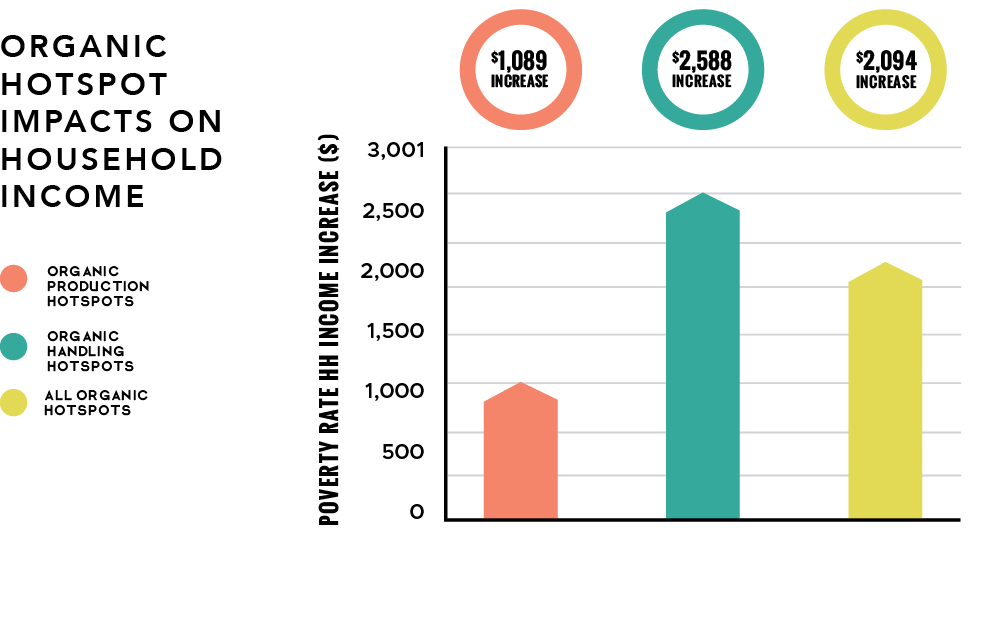

In fact, earlier in 2016, The Organic Trade Association released a report identifying a link between organic hotspots or counties with high levels of organic agricultural activity and reduced poverty and increased household income. The findings suggest that certain policies which promote organic agriculture can be included as rural economic-development tools.

“My results are surprisingly strong,” says Penn State agricultural economist, Ted Jaenicke, who published the work in collaboration with his former Ph.D. student, Dr. Julia Marasteanu. They compared counties that were similar in many varied ways except that one county was part of an organic hotspot and the similar county wasn’t. Jaenicke found that the presence of an organic hotspot, on average, leads to a county poverty rate that is 1.3 percentage points lower and a median household income that is $2,000 higher than in the non-hotspot county. There were no such benefits in general agricultural hotspots.

“The report matters because…local, state or national policymakers now have evidence that promoting organic agriculture to the point of generating a hotspot will have positive spillovers on the local economy,” says Jaenicke.

Such was the case for Maine Grains in Skowhegan, Maine, where they buy organic grains directly from local farmers, clean and process those grains into stone-ground flour and rolled oats, and market them to customers throughout the Northeast. Outside of her direct employ, President and CEO Amber Lambke estimates that some 400 people rely on the infrastructure surrounding her stone-milling facility for their livelihood. “The companies that are producing these processed goods are not just supporting growers, or the people making the food, those companies all have people doing finance, accounting, human resources, marketing, branding and IT,” says Justin Freeman, former general manager of Hummingbird Wholesale, a distributor that sources, processes, packages and distributes food products, of which over 90 percent are organic. “They are building products, but they are also building companies. We definitely see that in Eugene, Oregon and in the Northwest. Our industry attracts and builds a lot of talent.”

Nevertheless, the organic industry is continually plagued by insufficient supply. The OTA reported that growth in the organic market — which saw a record sales increase of 11 percent from the previous year — would have been greater if the supply would have been available. That leads one to ask why the demand for organic products hasn’t automatically sparked an uptick in the production of organic commodities. It’s not like an economic rebound isn’t needed. In fact, it’s desperately needed. While employment has begun to grow slowly in rural areas since the recession (one percent in 2014), population and labor force growth are near zero, according to Rural America at a Glance, an update published yearly by the USDA Economic Research Service.

So, what’s keeping more farmers, would-be commodities manufacturers, distributors and prepared foods companies from going organic and applying this pecuniary salve?

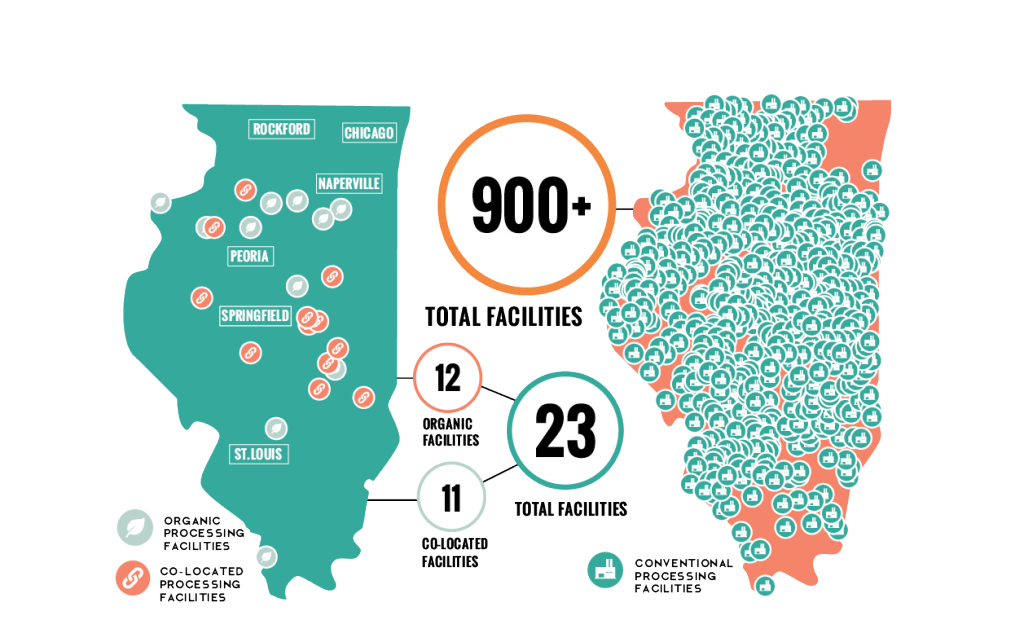

Building infastructure

The first challenge is a lack of infrastructure — millers, handlers and storage facilities — that make up an organic supply chain. “There is this whole invisible support system that needs to be certified to keep the integrity of products — many folks don’t think about distribution, contamination, processing facilities and packaging,” says Kellee James, founder and CEO of Mercaris, a company that publishes market reports and built a grain-marketing platform for growers to trade commodities online. “Organic opportunity is not just about production, its growth is associated with sectors of construction, manufacturing, distribution and more.”

The dearth of certified grain-handling facilities across the country is a big part of the problem, agrees Freeman. “[The organic supply chain] doesn’t have a robust market or storage system where we can send products that might need to sit a while until prices lower.” This is important given that farming is a climate driven industry.Transportation is another big part of that equation. The miles a farmer has to log to transport his grain to a mill can mean the difference between profitability and economic default.

Transitioning organically and financially

Once you decide to become an organic grower, your crop or livestock enters a three-year transitioning phase before it can be sold as certified organic. During this period, farmers put in the additional effort and costs associated with organic production but cannot benefit from increased profits.

The process can be financially trying, and therefore monetary support from banks, investors, certifiers, outreach organizations and governmental agencies by way of grants and loans is tantamount to their long-term success, says James. This type of support has been standard for conventional farmers but less so for organic growers. Programs like the USDA’s National Organic Program provides funding, which covers as much as 75 percent of an individual applicant’s certification costs, up to a maximum of $750 annually per certification scope. The AMS funds help to ease the burden of transitioning, but more is needed.

“Keep in mind that, organic businesses are businesses,” says James. “There is no one-size-fits-all financial incentive. That’s why local government can be so important in providing appropriate support. It might be tax-related relief or access to capital in the form of subsidized loans; it could be grants for the type of infrastructure most needed. The bottom line is it requires nuance and an understanding of local conditions.”

The Minnesota Institute for Sustainable Agriculture at the University of Minnesota is heavily committed to organic agriculture and has a great outreach program that financially supports transitioning farmers, says James, who shares her market data with the school at no cost.

But there are other ways that the government could chip in. For example, the 2018 Farm Bill promises to be one of the most significant policy issues for the 115th Congress, according to the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition. It suggests, among other things, that in order to help sustainable farmers create more infrastructure, Congress should adopt legislation, which could:

- Support beginning farmers by reforming crop insurance

- Preserve USDA loan funding for small and beginning farmers

- Enhance the Farm Credit System mission to better serve beginning and diverse farmers

Outreach along with certification

Certification can be a burden. Organic facilities have all the challenges of any other food-related business, plus the added requirement of documenting their organic handling practices such as maintaining separation and avoiding contamination from non-organic substances. But certifying organizations have historically been a godsend for organic growers.

“The most striking finding [in the OTA white paper] is that outreach and education activities by some organic certifiers has a big influence on the likelihood of a county being in an organic hotspot,” explains Jaenicke. “For example, I find that if 50 percent or more of organic operations in a county are certified by certifiers that provide outreach and education, then that county is almost 13 percent more likely to be in an organic hotspot.”

James says organizations that help reduce paperwork requirements, like the USDA’s “Sound & Sensible” certification process, or those that facilitate a streamlined certification process, like Oregon Tilth’s MYOTCO, an online record keeping database, need more funding to keep up their good work.

Collect and enhance market data

While building local infrastructure is important, constructing a digital infrastructure from local market data that is accessible anywhere is pivotal to helping the organic industry thrive.”Infrastructure isn’t just physical,” says James. “It also encompasses the knowledge and connections to help organic businesses be successful. Market infrastructure is key.”

Market data like Mercaris’s acreage reports can show where organic and grain handling infrastructure are, and what prices people are paying in certain areas. “I think the best data to boost organic infrastructure would be costs and returns data collected from intensive USDA surveys,” says Jaenicke. “But better pricing data would improve the costs and returns data for organic farms.”

Freeman believes that infrequent or incomplete participation in USDA surveys by growers may result in inaccurate assessments. “Unfortunately, the data available in the public sphere–on exchanges with minute-to-minute pricing are largely unavailable with organic,” says Freeman. “One reason we launched the Mercaris data service and trading platform was to provide more detailed and timely price information for growers and others involved in the organic supply chain,” says James. “We want to enable buyers and sellers to meet online, rather than having to find each other through word of mouth.”

Training and research by extension services

Finally, additional funding specifically for organic research and to train agents on organic at land-grant institution extension services helps develop expertise in the varying organic supply chains.

“The biggest investment that could be made to support the growth of organic as an economic growth engine is in the area of supporting organic extension agents,” says Freeman. “Extension services focused on conventional and GMO agriculture puts organic growers at a disadvantage.”

Freeman highlights organizations like Oregon Tilth, which provides support to Oregon State University by supplying a dedicated part-time staffer to instruct transitional farmers, but he says policy makers need to consider ways to pay for such expertise at schools nationwide. “I feel that education and outreach for organic agriculture still lags behind outreach for conventional, non-organic agriculture,” agrees Jaenicke. “Organic certifying agents, like Pennsylvania Certified Organic here in Pennsylvania, have been taking up some of the slack on outreach. Yet these outreach efforts by PCO and other certifiers are costly. [If] these outreach efforts by certifiers were cost-shared by a federal program, then organic farmers or transitioning organic farmers would have more support.”