Some revolutions have humble beginnings. This one started in 2012 when Angela Wartes-Kahl wanted a summer work shirt. She owns Common Treasury, a blueberry, livestock and fiber farm in Alsea, Oregon, certified organic since 1993. Her flock of English Longwool sheep supplied plenty of wool for winter apparel, but the appeal of knitted sweaters fades as temperatures rise in the Willamette Valley.

“I was thinking it would be nice to have a complete wardrobe,” said Wartes-Kahl. So she looked into other options. Oregon’s too cold for growing cotton. Flax — the fiber plant used to produce linen — seemed more promising. After researching the history of Oregon’s once-thriving flax industry, Wartes-Kahl took it as a sign. “I thought: I’m in Oregon, I can do this,” she said.

Photo by Micah Fischer

Oregon’s flax history

She had good reason to believe in the Northwest’s potential for growing flax. During the first half of the 20th century, flax was a flagship Oregon industry, so important that it merited an annual Flax Festival in Mt. Angel, complete with flax-themed floats and the crowning of the year’s Flax Queen (in 1938, her name was Maxine). But by 1950, fiber flax had nearly vanished from Oregon, and today the only flax grown in the Willamette Valley is harvested for seed, not fiber.

Oregon’s flax story is both local and global. The world’s best flax has always come from Europe’s lowlands: Belgium, the Netherlands and northern France. There, mild temperatures, fertile soil and a centuries-old textile industry have combined to create an industry known for producing exceptionally long and fine fiber flax used to create very high-quality linen fabric.

The Willamette Valley’s climate has many similarities to the climate of Flanders, Belgium, and in the early 1900s, the U.S. government decided that western Oregon might be the next global leader in the natural textile industry. So they started out with a captive audience: those in the penal system. Prisoners were enlisted to grow and weave flax fibers, producing household goods like tablecloths, napkins and placemats. The government established flax processing facilities where the crop could be retted (dampened or soaked), dressed, spun into thread, and woven into linen.

Over the following decades, the industry continued to grow. When World War II began, demand for flax skyrocketed to supply the factories manufacturing rope, netting, canvas tents and flak jackets for the war effort. In 1940, more than 18,000 acres of flax grew in the Willamette Valley. Fourteen mills processed it.

At that time, the focus was on quantity, and the people in northern France and Flanders were in no position to advise on best practices. “Quality standards were never really developed,” said Wartes-Kahl. When the war ended, Belgian mills ramped back up, and the Oregon industry declined as the U.S. moved toward synthetic fibers. By 1955, the last of the government-run processing facilities closed. With no place to take their crops, farmers quit growing fiber flax, bringing an end to the domestic industry.

A broken system

Before founding the Pacific Northwest branch of Fibershed, an influential nonprofit based in Marin County dedicated to reviving local fiber production, Shannon Welsh was a clothing designer. She’d always loved textiles, but became disillusioned with the current state of the apparel industry. “The more I learned about synthetic fibers and how they don’t decompose at all, the more natural fibers seemed crucial to get back,” she said.

We’re in the farm-to-table era, but local fiber is the last frontier. Unless you live in the cotton-growing regions of the South, acquiring locally produced fiber is a real challenge. Yet we’ve never bought more clothing. In 2014, Matthias Wallender, CEO of the textile recycling company USAgain, told The Atlantic that Americans buy five times as much clothing as they did in 1980.

The proliferation of low-cost, high-volume clothing brands like Forever 21, H&M and the Gap has transformed the apparel industry, requiring companies to churn out a dozen or more “seasons” worth of clothing each year. That means buyers need a vast quantity of fiber and fabric each month, and relationships with suppliers can be capricious, built on clothing trends that can shift in an instant. The natural fiber industry isn’t even close to being able to meet demand.

“After World War II, we just really let our industry go,” said Welsh. “Before I started working in apparel, I didn’t realize how broken our system was.”

As part of her work with Fibershed, Welsh and her documentarian husband, John Morgan, interviewed and recorded local farmers, artists and designers who were growing and working with natural fibers. And then, one day, she got an email. It was Wartes-Kahl, inviting her to come visit her personal flax plot.

The fiber revolution begins

Today, Wartes-Kahl and Welsh are friends, business partners and the co-owners and directors of Fibrevolution, a new business affiliated with Fibershed dedicated to bringing flax production back to the Willamette Valley.

Last year, Fibershed received a grant from Patagonia to help solve the fundamental puzzle of flax: Where do you start to revive an industry? After getting funding, one of the first things Wartes-Kahl and Welsh did was contact Alvin Ulrich, a global consultant to the fiber industry and president of Biolin Research Inc. in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, a company working to commercialize products from flax straw, fiber and shive (the cellulose-rich inner section of the flax plant).

In late 2017, Ulrich traveled to Salem to evaluate historic flax fiber and linen samples as well as the flax fiber Welsh, Wartes-Kahl and their collaborators had grown across 4.5 acres. That crop represented the entirety of the state’s fiber flax production in 2017. Because there are no processing facilities in the United States, they had pulled and processed the fiber by hand, just like the peasants in a Breughel painting. Yet the fiber produced looked long and fine, the right grade for making premium linen fabric, and Welsh and Wartes-Kahl were eager to get an expert opinion on their performance and the region’s potential.

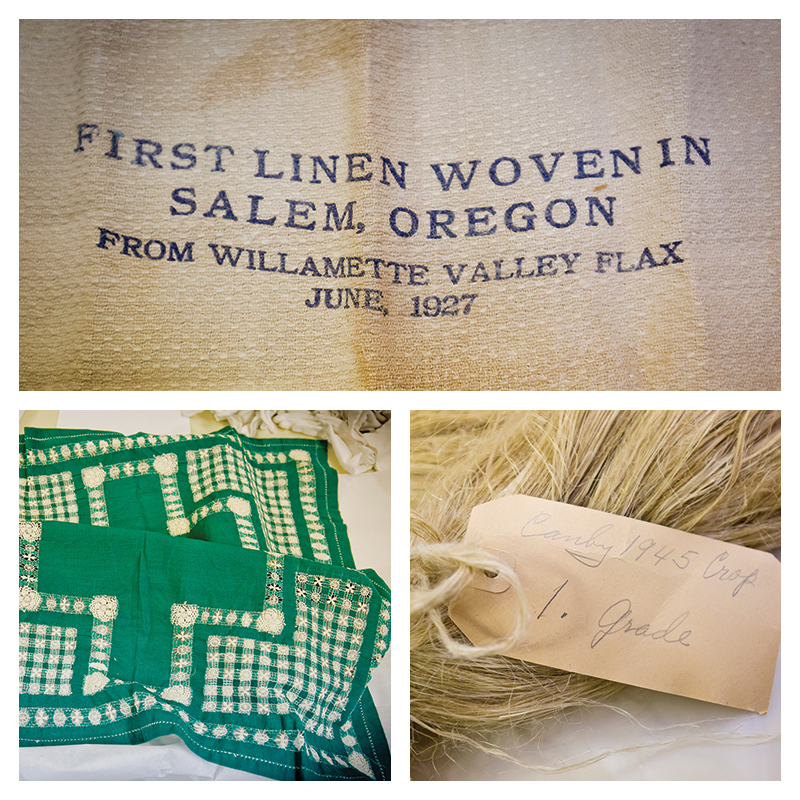

At the Willamette Heritage Center, a curator displayed box after box of Oregon-made linen and flax fiber. One held a surprisingly dainty green and white napkin-and-tablecloth set woven by prisoners a century ago. Another was full of spools of dyed linen thread, some with the price tags still attached. Ulrich reached into one box and pulled out a hank of fibers grown in 1945 in Canby, Oregon. He teased out a few individual fibers and held them to the light to assess them, murmuring appreciatively at their length and fine diameter.

Flax quality is determined by a number of factors, including weather, field conditions, water, human capital and the availability of processing equipment. In early 20th century Oregon, conditions were just right. “They had everything — they had the whole package,” said Ulrich. And, it seems, Oregon might still have what it takes to grow great flax. When he evaluated Welsh and Wartes-Kahl’s 2017 crop, he rated it a “nine, maybe nine and a half” out of 10, a major validation for their proof of concept.

Can flax come back?

Now, all that remains — and it’s a big “all” — is to re-establish the infrastructure to make flax commercially viable for Oregon farmers. It’s a multipronged problem. First, there’s precious little fiber flax seed available to American growers. Jenny Kling, a breeder at Oregon State University, is already hard at work at crossing several breeding lines from dehybridized F1s, and hopes to have enough seed to launch several one-acre test plots in 2019. Farmer Ralph Fisher at Fisher Ridge Farms in Sublimity, Oregon, plans to grow up to 18 acres of flax from existing varieties in 2018 to help boost seed supply.

At the same time, Wartes-Kahl and Welsh are aware of the absence of commercial harvesting and processing equipment, and they know that hand-pulling and field-retting flax isn’t a viable option for most growers. So this summer, they’re headed to Europe to search for machinery, including mechanical pullers, mills and dressing equipment. Belgium and France seem promising, but they’re also looking to the Czech Republic and Russia, which had a thriving long-line flax industry at one point.

“We’re focused mostly on servicing our region, which means we don’t want to get that big,” said Welsh. “We’re looking at midscale processing from flax to hanks.” Long-term, she dreams about creating a certified organic long-line linen mill, although right now putting agronomics first seems the best way to build a firm foundation for the industry. “We’re going to focus on the crop before we go into processing,” she said.

One of the most exciting things about flax as a crop is its versatility. Fine long-line flax is used to produce high-quality linen, which is used for apparel and household textiles. But short-line flax, also called tow, has lots of uses, too. Some plastics used in cars and airplanes contain fibers like flax tow to add strength without weight. It also has promise as an eco-friendly insulation material. Unlike fiberglass, it poses no health risks to workers, and it can be composted at the end of its life. And unlike cotton, it’s stiff enough to stay in place inside vertical structures. Even better, it’s naturally flame resistant.

Ulrich also said that dual-purpose flax crops (fiber and oilseed) are a viable option for farmers. He’s used flax grown for oilseed as a fiber material and achieved “wonderful” results, although oilseed flax is usually more widely spaced in planting and therefore not quite as productive for fiber. “It’s certainly possible to have a dual-purpose crop,” he said. “The yields are just lower.”

What will it take?

The wholesale revival of any industry is a massive undertaking, let alone one that’s been moribund for 70 years. Welsh and Wartes-Kahl think it will take a combination of grassroots support and end user buy-in to get the project fully off the ground. “What scares people away is that we’re starting at the very beginning,” said Welsh. “The question is always, ‘Why is nobody else doing this?’ I think it’s going to take a big brand throwing their money on the table and helping rebuild some infrastructure.”

It’s a tall order, but the timing might be right. Major apparel companies have never been more interested in sustainability, and consumers who understand the importance of local food are poised to see the same value in local fiber. There’s a long way left to go, but after a promising start, Welsh and Wartes-Kahl have faith that the threads will start to come together.