Collaboration is crucial for developing sustainable solutions in any political arena, and pollinator health is no exception. City council members, scientists, business owners, educators and residents are coming together to enact municipal, and to some extent national, pollinator protection policies. Local ordinances are strengthening neighborhood awareness of pollinator protection, but it’s too soon to tell whether these grassroots efforts can drive broad-based change.

Neonictinoids and pollinator health

Populations of honeybees and other pollinators have declined in recent years, with scientists reporting that beekeepers lost 42 percent of their hives in 2014. Declining habitat, parasites, diseases and agricultural pesticides are suspected causes. Two studies released in 2012 pointed to a new class of systemic insecticides applied to seeds, called neonicotinoids (neonics), as possible contributors to pollinator decline. In bumble bees, exposure to neonics causes a significant loss of queens. In honeybees, another insecticide in the category obstructs foragers’ ability to find their way back to their hives.

Researchers say these findings are cause for concern, especially given neonics’ propensity to affect the entire plant system, from seed to stem to nectar and pollen.

“It’s not surprising that insecticides, which are designed to kill insects, pose a risk to pollinators,” said Aimee Code, pesticide program director at the Xerces Society. “But with the introduction of neonics in the past couple of decades, the risks have increased and changed in unexpected ways. We are seeing that neonics, even at low levels, can cause harm. And since they are systemic, these compounds can move up through a plant over the course of months or even years, increasing the likelihood of exposure via pollen and nectar contamination.”

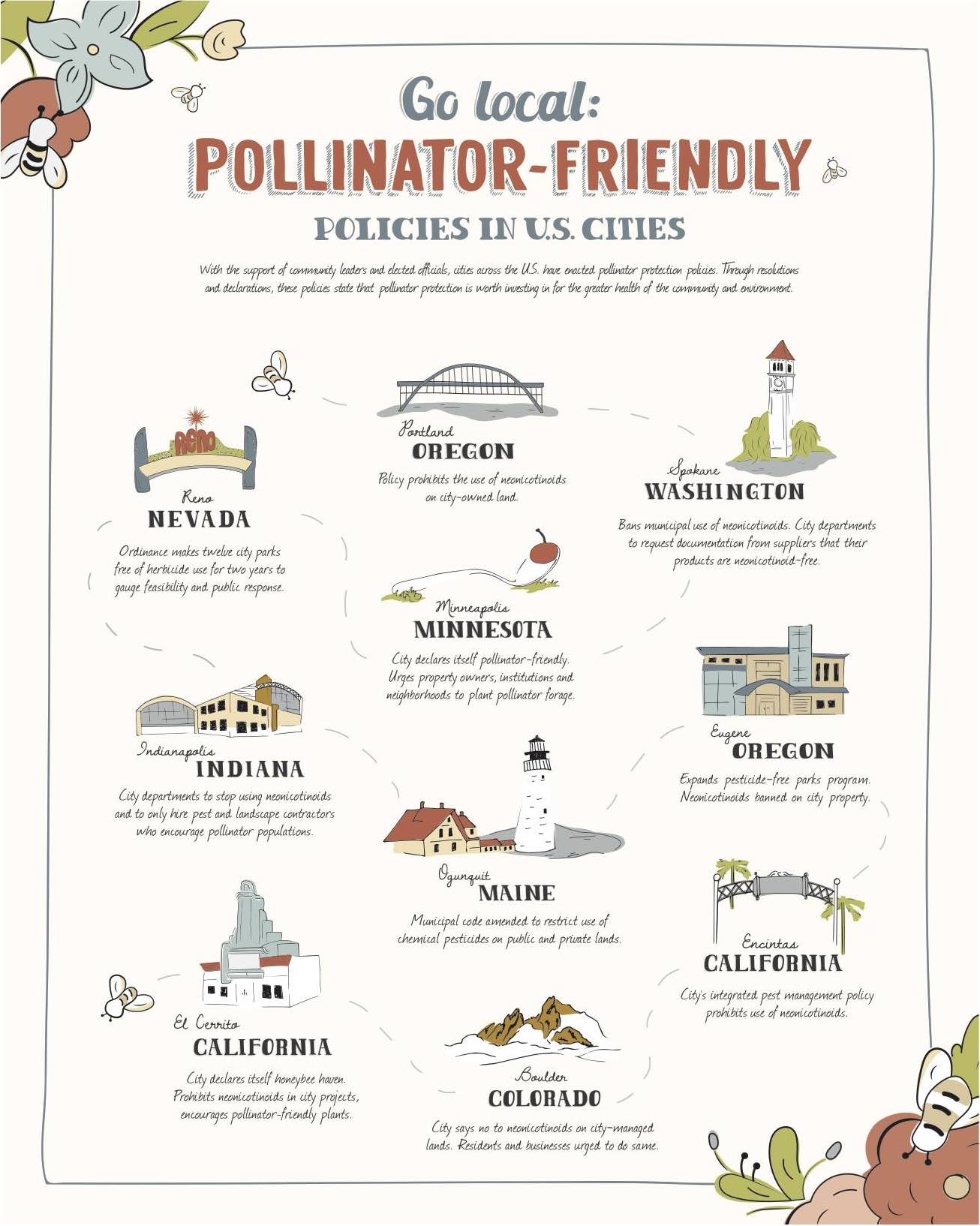

In response, policy makers are enacting regulations to reduce or eliminate the use of neonic insecticides. To date, these policies, applied locally, have had little impact. But they’re a first step in addressing a larger, national arena.

Pulse on national pollinator protections

Over the past five years, support for pollinator health grew at the federal level, with some pollinator advocates even calling Obama the “Pollinator President.” In 2013, the EPA released an advisory and two letters to pesticide registrants with requirements to change labels on neonic-containing products to better protect bees, including specific limits such as “do not apply this product when bees are foraging.” Then, in June 2014, the Obama administration signed a memorandum to create a federal strategy to promote the health of honeybees and other pollinators, including native bees, birds, bats and butterflies. The memo cited pollinators’ contributions to economics, food security and environmental health, and established the Pollinator Health Task Force, co-chaired by the Secretary of Agriculture and the EPA Administrator.

In 2015, the task force released the National Pollinator Health Strategy that included a science-based Research Action Plan, public education, public-private partnerships and increased development and improvement of pollinator habitats. Pollinator gardens were constructed at federal buildings and the USDA and Department of Interior issued a set of Pollinator-Friendly Best Management Practices for Federal Lands.

Just this January, the EPA published preliminary pollinator-only risk assessments for neonic insecticides, stating that most approved uses do not pose significant risks to bee colonies. Spray applications to specific crops, however, may pose risks to bees that come in direct contact with the residues, warranting the exploration of alternative ways to measure exposure via pollen and nectar. It’s uncertain whether the new administration will uphold Obama’s Pollinator Health Strategy.

Pollinator protection in local jurisdictions

Some cities across the United States have implemented their own policies and resolutions to support pollinator health. In Boulder, Colorado, for example, these policies stemmed from the public’s desire to formalize programs already underway to bolster community education.

Restoring and protecting land is part of our local culture; it was a natural fit for us.

Boulder was one of the first cities to adopt an integrated pest management (IPM) policy in 1993, as well as a neighbor notification ordinance for pesticide applications. The pollinator protection resolution passed in 2015 formalized the city’s refusal to use any neonic-active ingredients on any parks, open spaces or landscapes and urged all public and private parties to adopt the same.

Even with a resolution in place, the city lacks the authority to restrict pesticide applications on private property (this would require state-level regulation). The ordinance is largely a public display of support for pollinator health.

“One of the greatest benefits of the formal policy is that it provides more backing for public education about the importance of pollinators, as well as ecosystem health and biodiversity,” said Abernathy. “We have implemented a pollinator appreciation month each September, including a film series, panel discussions and activities for all ages. We aim to keep people engaged who are already committed to planting pollinator forage and to enroll new audiences to increase their awareness of the role pollinators play in our local food systems.”

City staff collaborates with local libraries and universities to host literature festivals and speaker series that help raise public awareness about pesticide use on water systems and biodiversity. They have also created alliances with local seed suppliers, microbreweries and restaurants that feature special beverages and dishes made from pollinator-friendly ingredients.

In Milwaukie, Oregon, the pollinator protection ordinance passed in April 2016 halts the use of neonics on public property within city limits. Like the Boulder resolution, the policy does not apply to private property.

“The most useful thing about our resolution is that it sends a message to the community that we are taking the issue of pollinator health very seriously,” said Milwaukie Mayor Mark Gamba. “Local ordinances lend legitimacy to what could be viewed as a fringe movement. With laws like ours in place, activists can take these examples and use them to add power to their statewide and national efforts.”

City policies are bolstering local awareness of the importance of pollinator protection, yet the movement remains largely grassroots with little municipal power to enforce public regulations.

This is where state governments come in. Minnesota is paving the way with Governor Mark Dayton’s executive order that requires farmers to verify their need prior to using neonic pesticides. Furthermore, the state’s Department of Agriculture will also increase enforcement of regulations on the use of any pesticides that harm bees.

While city planners, environmental groups and residents have supported city policies, statewide mandates are likely to cause contention, especially with some farmers and businesses. The 2015 adoption of new regulatory requirements in Ontario, Canada, for selling and using neonic-treated seeds has caused tension between policy makers and grain farmers. According to an Ontario seed company executive, many farmers are either ignoring the restrictions or evading them by switching to alternative insecticides not covered by law.

Beyond policies: residents and beekeepers weigh in

The regulatory reach of policy efforts remains small, but anecdotal evidence suggests that local ordinances and EPA labeling requirements are broadening awareness of the importance of pollinator protection. Legalizing urban beekeeping in Oregon towns like Ashland and Medford has helped create positive relationships among community members and with their bees.

“At the city council meeting, a veteran got up to testify, saying that beekeeping is the only thing that helped her heal from PTSD,” said Bee Girl Executive Director and Southern Oregon Beekeepers Association Regional Representative Sarah Red-Laird. “Another older gentleman got up to share that bees make him feel like he has a friend and a purpose.”

Backyard beekeeping policies help empower residents to use their backyards in meaningful ways. “Resident beekeepers are some of our best advocates for bees and pollinators,” said Red-Laird. “Keeping bees alive is hard. If their bees die from pesticides, it ignites passion in people to take local action.”

It’s not just in backyards where policies support greater awareness of pollinator health. For John Jacob, a commercial beekeeper and president of the Southern Oregon Beekeepers Association, stricter labeling of pesticides has benefited his business.

“Farmers are becoming more careful about what they spray and when,” said Jacob. “About 40 percent of my income comes from pollination services, so if growers aren’t careful, I could lose my entire life’s savings.”

Jacob and organizations he works with also encourage farmers and homeowners to plant forage around their fields and properties so bees and other native pollinators have access to more diverse pollen and nectar (as compared to monocrops or lawns).

“A lot of people want to help,” said Jacob. “How they choose to landscape can make a big difference for pollinators.”

To learn more about how you can support pollinator health in your own backyard, visit the Xerces Society Pollinator Conservation Gardens Resource page.