Farmers are having a tough time finding laborers these days. Domestic farm workers are scarce, as many age out of the labor pool and few are eager to replace them. Half of all farm workers are undocumented, according to USDA figures, which are likely underestimated. Without this undocumented labor, large segments of the agricultural economy would collapse.

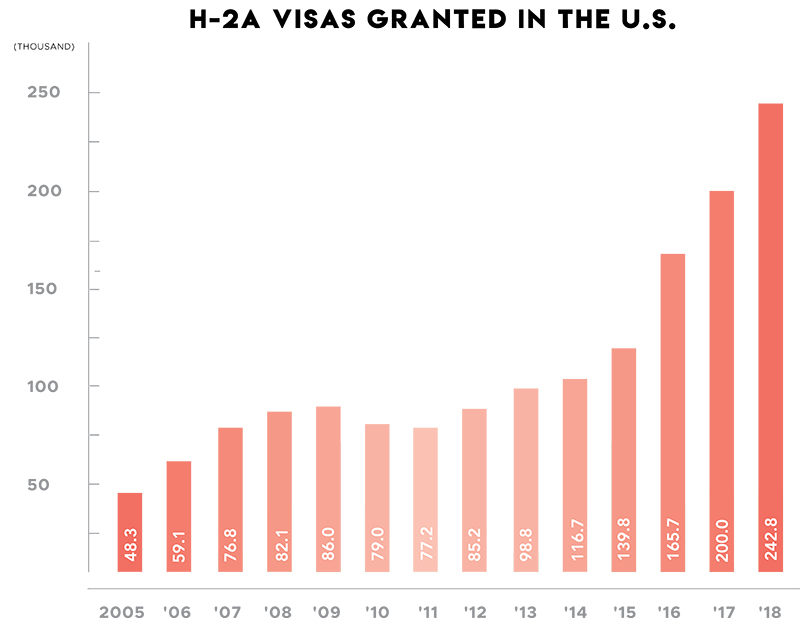

Now, as ICE raids and deportations become a fixture in headlines, farmers fear the possibility of losing their undocumented workforce overnight. Many farmers have turned to the H-2A visa system to secure legal labor. The number of H-2A visas granted has grown fivefold over the past 13 years, from 48,000 in 2005 to 243,000 in 2018.

The H-2A program was designed to allow farmers to fill gaps in domestic labor with seasonal guest workers from abroad. The program is widely regarded among farmers as expensive, cumbersome and bureaucratic, while farm workers’ groups contend that the system leaves workers vulnerable to abuse. Despite the program’s challenges, in a tough labor market, farmers associations and cooperatives are finding ways to make the H-2A system workable.

A frustrating system

For farmers to successfully apply for an H-2A visa, they must first wade through a sea of paperwork administered by multiple federal agencies, including offices in the Department of Labor (DOL), Homeland Security, State, and Agriculture (USDA), as well as state agencies, each with their own timelines. In addition to visa requirements, the producer must fulfill a specific set of employment advertising requirements to demonstrate that there are no U.S. citizens willing to do the work.

“You start from scratch every year, and go through the application process,” said Joel Anderson, executive director of Snake River Farmers Association, which helps its members file H-2A applications. “Consistently there are government and agency delays, roadblocks and barriers. One year it might be the DOL, because they lack funding…another year it might be state agencies. They don’t coordinate. Each one lives in its own box, and we have to cross from one to the other in navigating the system.”

Once an application is approved, the producer must provide for the transportation, housing and food for the H-2A guest worker. Workers must be paid the higher of the statutory minimum wage or DOL’s adverse effect wage rate (AEWR), which is calculated annually based on median pay in USDA survey data, and is supposed to avoid undercutting domestic workers. The housing must be inspected by state agencies, and these inspections vary from state to state, adding another layer of regulatory complexity.

The costs of the H-2A program can stack up fast for small farmers, according to Mary Jo Dudley, a faculty member of Cornell’s department of development sociology, and director of the Cornell Farmworker Program.

“Since H-2A workers receive the federally determined ‘adverse effect wage rate,’ or AEWR, their hourly wages are often higher than the state’s farmworker minimum wage,” said Dudley. “In addition to AEWR, H-2A contracts require that the employer pay for round-trip transportation from their home country. Because the housing is strictly regulated, there also tends to be greater investment in housing.”

But despite these headaches and expenses, farmers continue to apply, primarily because relying on undocumented labor poses its own risks.

“In the middle of a harvest, you can’t lose all your workers to deportation, you’ll lose your crop,” said Dudley. “So I think the number one factor [for the growth in H-2A] is immigration enforcement. Honestly, that is at least part of the reason.”

Getting by with a little help

So how are farmers making the H-2A system work for them? While large producers can use dedicated staff, small farmers cannot navigate the H-2A system alone. Some pay farm labor contractors to supply H-2A workers, but increasingly, many small-scale farmers have joined associations like the Snake River Farmers Association or the North Carolina Growers Association that offer centralized services to navigate the paperwork and manage compliance, and even coordinate transportation and housing for H-2A workers. These associations can be legally structured in several ways, as nonprofit or for-profit entities, and can file as the joint employer with the producer, or as an agent of the producer.

“The bigger producers can hire staff that can do it internally, whereas the smaller guys have a tougher time,” said Anderson. “We function as an agent that handles the preparation and submission of paperwork to the appropriate agencies. As an association, we also have a focus on compliance. We make sure that members are following the regulations. They as members own the organization.”

Having an experienced, centralized agent assisting with the process can make the H-2A process achievable, even for small farmers. The majority of the Snake River Farmers Association employ less than five H-2A workers.

Going a step further to spread the pain, small farmers can share a work contract between two or more farms; these joint arrangements can be structured in several ways.

“We have some producers who are joint employers, so they’ll share workers who will bounce back and forth between farms,” said Anderson. “They’ll say, ‘We’ll both sign this paper, and you’ll use them this time, and I’ll use them that time, and we’ll make sure we give them enough hours for the contract, so we meet that requirement.’ What you’ll find is that it works if they’re family and they’re used to working that way anyway. They’re just introducing the H-2A aspect, or they’re neighbors, and they understand each other’s business.”

The farmworker’s view

In addition to the inefficiencies and headaches the H-2A system can cause producers, the program has drawn much criticism from farmworkers’ rights groups as well as domestic labor unions. Groups like Farmworker Justice and the Global Workers Justice Alliance point out that the way the worker’s visa is tied to a specific employer leaves H-2A workers vulnerable to abuse, since employers can threaten to send workers home. This point was echoed by a U.N. special rapporteur on human trafficking in 2016.

There have been some notable tragedies in the H-2A system, such as the death (later attributed to natural causes) of H-2A worker Honesto Silva Ibarra, which prompted some of his co-workers to go on a one-day strike in 2017, protesting what they said were poor working conditions. In 2015, the Government Accountability Office called for increased protections and enforcement to prevent abuses of H-2A workers, and reissued that call in 2017.

“For H-2A farm labor contractors in California, I think it would be good for the H-2A employees to have an orientation on the first week of the workers getting here, to ensure that the workers understand the working conditions, to ensure that they get a copy of the contract, to make sure that they know that the employers cannot hold their visas — which is a sign of human trafficking — and to make sure that the workers know who to contact when they have a question or complaint regarding health and safety concerns or wage complaints, said Cornelio Gomez, foreign labor and agricultural outreach manager at the California Employment Development Department, a state workforce agency that processes H-2A job clearance orders. “After all, the H-2A workers have rights, since they are in California legally.”

Fixing the system

Though many farmers have found ways to make the H-2A system a way to secure legal labor, and many farm workers have come back to the same farm for many lucrative seasons, nobody would describe the system as perfect.

There is hope of improvement at the margins. Recently, efforts at the federal level to modernize the job advertising component of H-2A have made the system more manageable.

Several organizations have developed proposals for reforms or alternatives to the H-2A system. Many proposals, such as an alternative visa designed by the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition and the Community Alliance of Family Farmers, focus on making visas portable, so that they are not tied to a specific employer. This could reduce the risk of employers threatening to send workers home, and could allow employers to draw from a pool of potential workers who are already certified to work in the country.

In many ways, a path to legal status for those who currently work in the U.S. without authorization makes the most sense.

“The myth of farmworkers as unskilled workers is exactly that: it’s a myth,” said Mary Jo Dudley of Cornell. “They have skills. To continue agriculture uninterrupted, the best thing would be to regularize the status of people who are workers on farms who don’t have status. I don’t think tweaking H-2A is going to be a solution for agriculture. If you think about it, if you have someone who has three, five, 10 years experience, you want to keep those people. So that should be your highest priority. How do you keep those people?”

In the current political climate, though, comprehensive immigration reform of the kind that could bring structural changes seems like a fantasy. Farmers and farmworkers will likely have to live with this current system for the time being. Fortunately, tweaks to the system are in the pipeline, and innovation by farmers associations and cooperatives have made a cumbersome system more manageable.