From the perspective of our vacant celebrity culture, it’s amazing that a plant breeder once was the most celebrated, acclaimed and polarizing personality of his time.

Luther Burbank (1849-1926) was a brilliant horticulturist who developed over 800 varieties of fruits, vegetables, nuts, berries, grains and cactuses, and he became a famous author and speaker. He won international acclaim and was considered one of his era’s most brilliant lights. Later, his heretical views vilified him.

Born, the 13th of 15 children in Lancaster, Massachusetts, Burbank picked up the love of gardening from his mother. As a young man, he was drawn to study medicine until his father’s death changed his family’s fortunes. Soon, he focused his considerable energies on the garden and began what would be a life-long passion.

Success

At age of 18, Burbank was experimenting on the family farm, when he read Charles Darwin’s book, The Variations of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. The experience was transformative. Burbank later remarked that, “While I had been struggling along on my experiments, the great Master had been reasoning out causes and effects for me, and setting them down in orderly fashion. By discovering the stored up heredity of the plants, and selecting those suitable to his purpose, and changing the environment to encourage the development of the traits he desired in his finished product, the plant breeder produces new plants. Thus a process that would have taken nature centuries to accomplish, may be done in a comparatively few years by man.” Burbank learned the principle of cross-breeding and selection as a means of changing the characteristics of plants.

At 22, Burbank bought his own truck farm and put more acreage under experimentation. Seeking to improve the common Irish potato, Luther grew and observed 23 potato seedlings from an Early Rose parent. One seedling produced many large tubers and held the promise to counter future potato blights. The Burbank potato was marketed in 1871 and is the ancestor of the Idaho Russet. Luther sold the rights to the variety to a Massachusetts seed man for $150.

With the sale of his farm adding to his small fortune, he moved to California where a few of his brothers lived.

To someone from central New England, Santa Rosa county blew his mind. He wrote that this was, “The chosen spot in all this earth as far as nature is concerned.”

Burbank soon established himself as a successful nurseryman with a four-acre experimental garden and a 40-acre farm in neighboring Sebastopol to begin his life’s work in earnest.

In 1881, a wealthy Petaluma banker approached him with a near impossible task to deliver 20,000 prune trees for fall planting. Burbank set to work with a process called “June-budding;” grafting prune buds on to early budding almond trees. News of his success spread, and he became known as the “Plant Wizard” during the rise of domestic large-scale fruit production and the refrigerated railcar — a time known as Agriculture’s Golden Era.

Burbank was considered a genius for unlocking plants’ hidden potential. He sensed what people wanted in food and flowers. He developed the Shasta daisy, the fire poppy, the “Flaming Gold” nectarine and the freestone peach. He used hybridization and grafting, cross-breeding different plants, and cross-pollination.

He had an easy personality, and would answer queries from people across the fence as he worked his gardens. Area farmers diversified their plantings based on his counsel. His plant catalog–mailed to a few hundred domestic and foreign nurseries–fueled his fame. New Creations in Fruits and Flowers was richly illustrated with photos, offering 250 new varieties. His prices were up to $3,000; each variety represented up to 10 years of work. Orders came flooding in, but he had to market existing stock to keep up with demand. Luther became an early advocate for plant patent laws that he would never see in his lifetime.

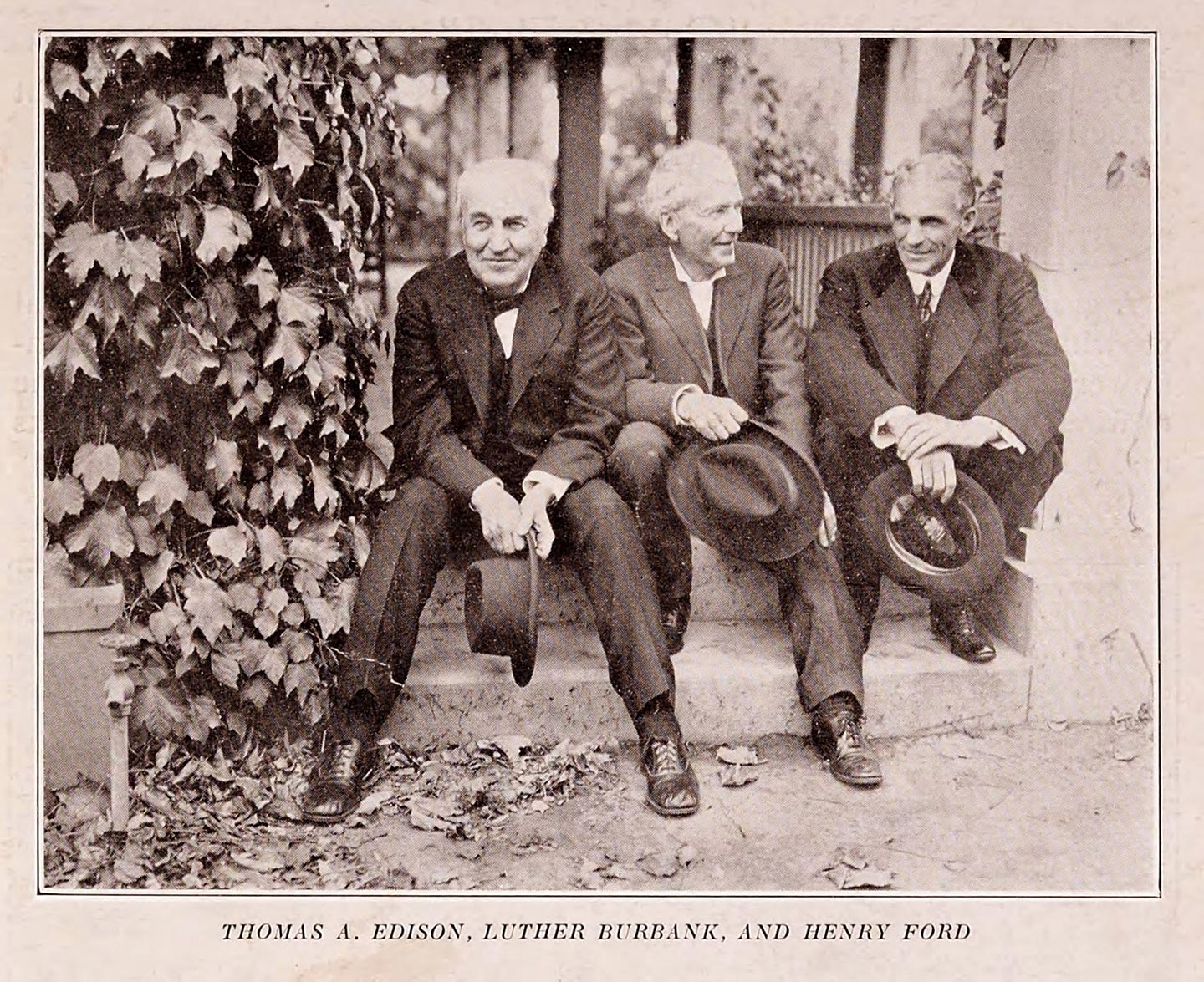

As his fame grew, he became friends with celebrities Henry Edison, Henry Ford, Helen Keller, William Jennings Bryant, the King and Queen of Belgium and Jack London.

London ran an experimental garden nearby and dreamt of a spineless cactus for livestock forage in the Southwest. Burbank soon bred just that, further adding to his fame.

As the years went by, Burbank and his (considerably younger) wife Betty remained childless, and devoted to the plants in their care.

Controversy

In 1907, Burbank published The Training of the Human Plant in which he wrote, “Just as a plant breeder notices modifications, when he joins two or more plants from widely separated quarters of the globe…so we hope for a far stronger and better race if the right principles are followed, a magnificent race, far superior to any preceding it.”

Eugenics — the idea that human beings can be intentionally managed to select for desired genetic traits — enjoyed wide social acceptance in his era, prior to Nazi Germany putting it into practice.

Good idea for plants, bad for people.

Apostasy

Luther was a life-long Freethinker and fan of Robert G. Ingersoll, who kept his views private, until John Thomas Scopes, a high school teacher in Tennessee, was tried for the “heresy” of teaching Darwin’s evolution.

The “Scopes Monkey Trial” in 1925, “Aroused him to a conviction that he ought to speak out, without mincing words, and declare for truth,” according to Burbank’s biographer Wilbur Hall. Shortly after, Henry Ford publicized his own views on reincarnation. The San Francisco Bulletin, interviewed Burbank about his reaction to Ford’s ideas. He responded with doubts about an afterlife, “A theory of personal resurrection or reincarnation of the individual is untenable.” The headline ran “I’m an Infidel, Declares Burbank, Casting Doubt on Soul Immortality Theory.” In a later interview, Burbank insisted he had checked the dictionary. “I know what an infidel is, and that’s what I am.”

He went on to publish Why I Am An Infidel, and The Harvest of the Years, with Wilbur Hale. Burbank wrote, “The clear light of science teaches us that we must be our own saviors, if we are to be found worth saving.”

A fire storm of condemnation followed. Thousands of hate letters arrived. Burbank responded to as many as he could.

According to Hale, “What killed Luther Burbank was his baffled, yearning, desperate effort to make people understand. His desire to induce them to substitute fact for hysteria drove him beyond his strength.”

He died shortly after, at age 77.

Legacy

Burbank’s work spurred the passing of the 1930 Plant Patent Act four years after his death.

Today, the Luther Burbank Home and Gardens is a 1.6-acre city park and a historic downtown Santa Rosa landmark. The city celebrates its Luther Burbank Rose Parade and Festival annually.

The Idaho Russet potato continues to be the world’s most common potato.