The 2018 farm bill has opened the door to U.S. hemp production for the first time in nearly 50 years, presenting opportunities for veteran farmers interested in cultivating a previously prohibited crop and attracting a new demographic of growers to American agriculture.

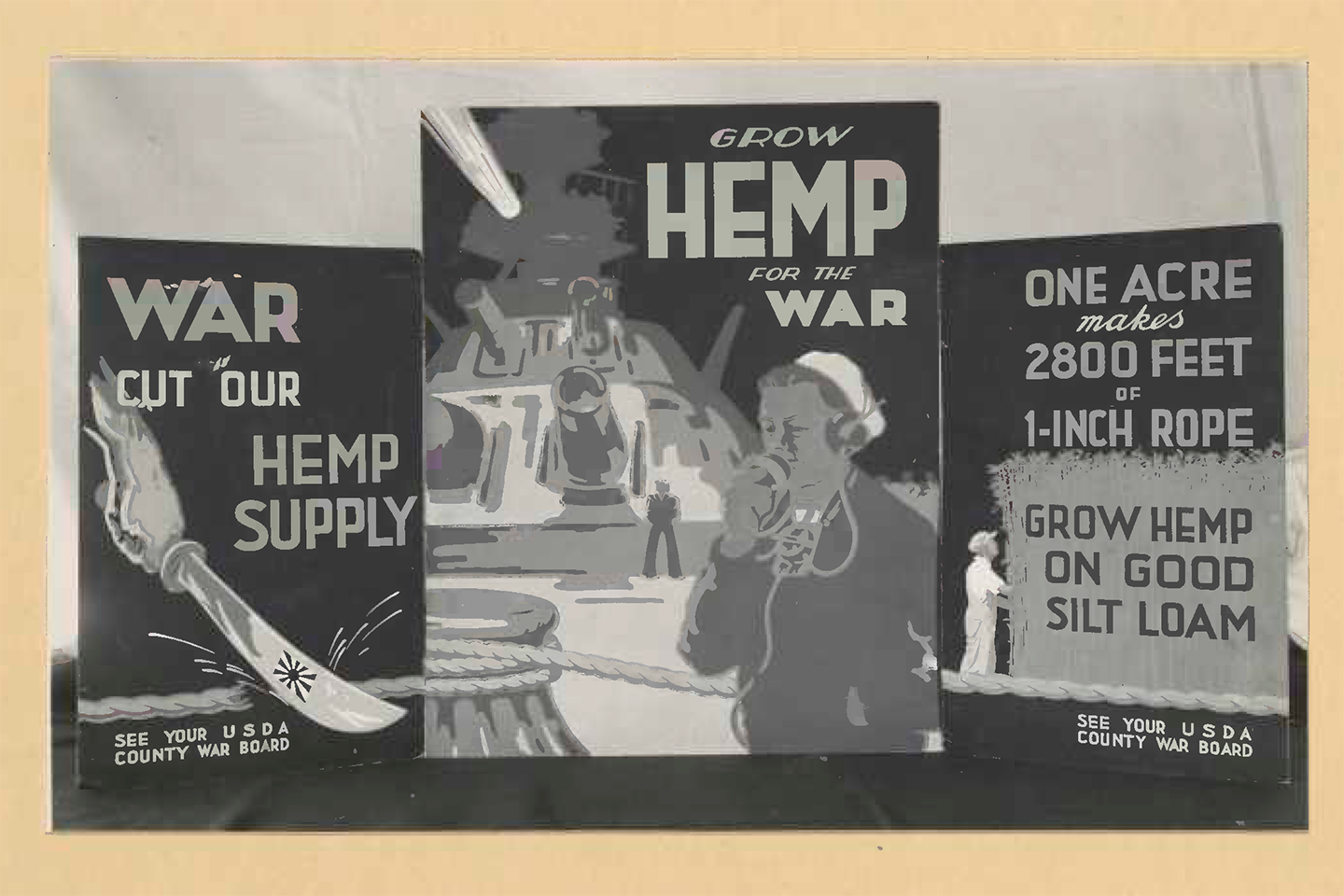

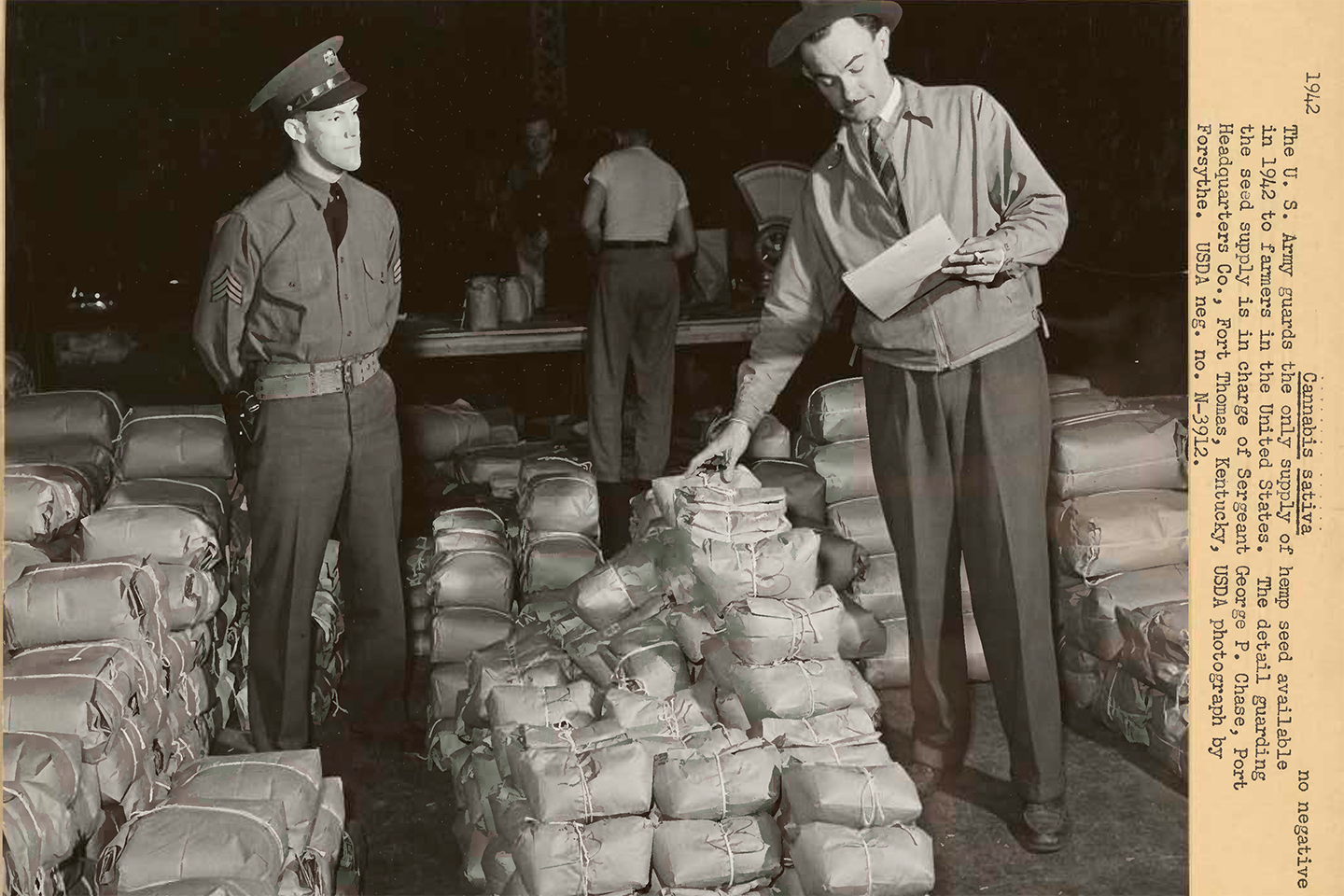

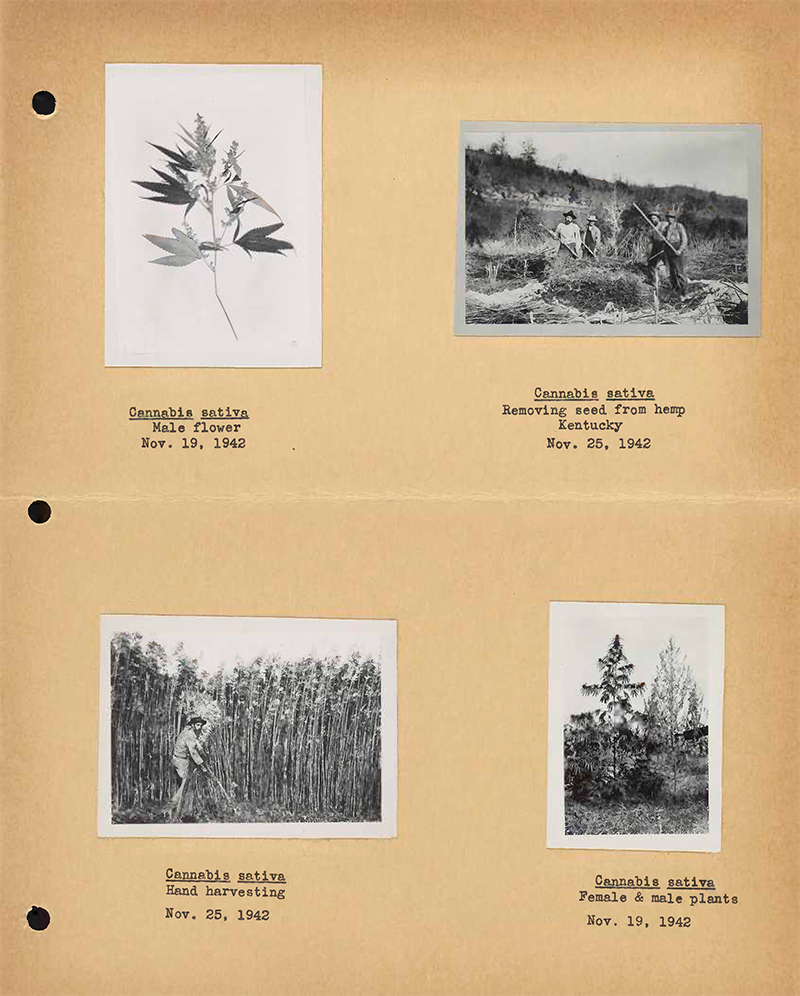

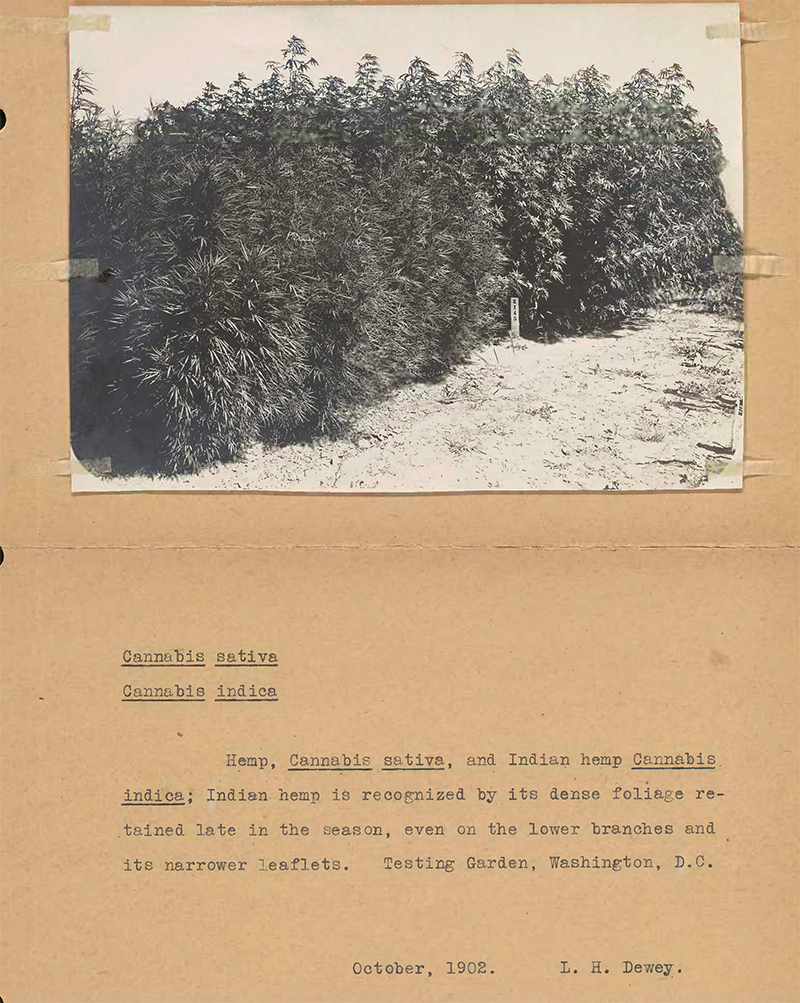

In the past — before it was criminalized — hemp was grown for fiber, grain, cordage and cloth. Despite its versatility, demand for and supply of the plant varied widely. In 1915, for example, U.S. hemp cultivation amounted to only 8,400 acres. Just two years later, because of the need for hemp products caused by World War I, 41,000 acres were in production. But by 1933, the United States had only 140 acres, as hemp was eclipsed by cotton and imported materials such as abaca, wood and sisal, which were cheaper and had other desirable properties. The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, which banned marijuana, was hemp’s last straw. Even though the act focused on stopping cannabis rich in tetrahydrocannabinol (THC, the compound known for facilitating highs), hemp was affected because it was the same type of plant.

Hemp growers got a temporary reprieve during World War II, when hemp products were necessary for the war effort. In 1943, 146,000 acres were under production for hemp fiber, with another 40,000 used for grain. However, by the 1950s, the United States would not have enough acres of hemp to even register in the eyes of the Department of Agriculture. No one grew it. Today, people still confuse it with its smokable cousin.

Not Your Grandfather’s Hemp

Today’s hemp farmer is less interested in the plant’s physical utility and more focused on its chemical contents, such as cannabidiol (CBD), which can be crafted into products to alleviate maladies such as migraines, inflammation, seizures, multiple sclerosis and other medical conditions.

Hemp and marijuana are both cannabis, and they contain THC and CBD, the compound used in medical applications. However, hemp must not contain more than 0.3 percent THC by law, whereas marijuana may have 25 percent THC — or more. In other words, hemp will not get you high.

Regardless, America’s extended break from hemp production created an agricultural knowledge gap that new growers are rushing to fill. Crops such as wheat, corn and even soy have been grown long enough that best practices have evolved. Farmers know what works and what does not. This is not the case with hemp. Everything from soil composition to regional preferences and pest management is still being discovered.

“We’ve got a lot of time to make up for,” said Eric Walker, an assistant professor of plant sciences at The Highland Rim Research and Education Center at the University of Tennessee’s Institute of Agriculture. “Our producers need information that has been verified in multiple locations over years, and they need that right now. And that’s impossible to produce right now. All we have is a snapshot at best.”

Hemp production shares some important traits with tobacco, said Walker, which he specializes in. He later added “specialty crops” such as industrial hemp to his repertoire.

“What I didn’t realize until I started working with hemp is that I took a lot of things for granted with other crops,” he said. “I think other people did, too. They just didn’t know, hadn’t thought about it.”

This knowledge gap is why the hemp industry needs people like Brian Koontz, the industrial hemp program manager for the Colorado Department of Agriculture’s Division of Plant Industry. He previously worked in the marijuana industry to ensure public safety through compliance and routine testing for pesticide residues. Today, he is focused on strengthening the regulatory framework for hemp and establishing standards of excellence for the hemp supply chain, such as CBD-level testing and safety procedures that will keep consumers safe and ensure they are paying for a fair product. He also works with other industries, from transportation and marketing to banking, insurance, and research and development.

“It’s challenging,” he said. “Some of these industries are just beginning to cooperate more fully with hemp producers. At one point, some couriers wouldn’t ship it, so it was hard for people to access seeds. Banks usually either refuse to work with producers or they charge inflated insurance rates because the FDIC doesn’t cover hemp. Marketing has been tough; we’re working hard to separate hemp from marijuana in the general public’s understanding.”

Farmers See Opportunity

But lack of production knowledge and incomplete support from partner industries is not stopping farmers. People are eager to start growing. Consider Colorado. In 2014, the state had 1,811 registered acres of hemp and 259 registered growers. Last year, it had 30,950 acres and 1,075 growers.

“And we already have close to 60,000 acres registered for this year,” said Koontz. “We could end up at 70,000 or 80,000. People are climbing on board to grow.”

Mason Walker is taking full advantage of hemp’s rebound. He was a journalist for seven years, when he covered the end of cannabis prohibition in Oregon. In 2015, he began working on a friend’s CBD-focused cannabis farm, and two years later, he became CEO of East Fork Cultivars. Its mission is to develop and preserve sustainable, sun-grown farming methods to produce high-quality, genetically diverse, CBD-rich cannabis and to craft hemp with a commitment to environmental responsibility, science-based education and social justice.

“We grow therapeutic-grade, flower-focused hemp that’s bred from more traditional cannabis plant lines,” said Walker. East Fork’s large-scale breeding program allows it to create new varieties of hemp and marijuana. “We’re breeding for diversity,” he said.

That diversity is reflected in the cannabinoids and terpenes in the plant. Cannabinoids are chemicals that can affect neurotransmission in the brain via the body’s endocannabinoid system. Terpenes are compounds found in the essential oils of cannabis and other plants such as citrus and conifers. There are countless types of cannabinoids and terpenes, and together they can craft unique profiles.

“We exist to create plant-based therapeutics that people can use for efficacious, therapeutic medical applications,” said Walker. “That’s how we got started, and that continues to be our focus today.”

He’s an unapologetic hemp booster. “This is a field that’s attracting a lot of passionate and intelligent people and researchers,” Walker said. “Botanists and chemists, people who could be working on anything — and they’re working on this plant because they’re excited about its potential.”

Not all the hubbub is about medical usage. East Fork is talking with apparel companies about using hemp fiber in their clothing, turning what is essentially a waste product in its flower-focused cultivation practices into a higher use than compost.

Koontz, meanwhile, sees hemp as a driver of sustainability. As he and his team continue to create policy, they can tie hemp production to strong land stewardship practices.

“Hemp can be very productive without having a large impact on the land, like some higher yield crops might,” said Koontz. “This gives it a lot of potential to continue affecting other industries. I think the energy industry will grow and water resources will change, and even other things will continue to develop, like nutrient technologies. The education sector will change, too, as it shifts into teaching more growers, and hand in hand with that will come more technology and IT.”

While the future of hemp is unknown, it seems that Americans have only begun to tap into its potential, with no signs of slowing down.

“Hemp is an interesting crop to work with, and I think a big reason is because it’s cannabis, closely associated to marijuana, and that has a really important place in our country’s history culturally,” said Eric Walker. “The United States is infatuated with cannabis, and I’m not saying that’s a bad thing. Out of all the crops I have worked with, people are more passionate about hemp than any crop I’ve ever been around. The good thing about passion is it drives action, and we’ve witnessed that.”