Rufus Isaacs is a professor of entomology and Extension specialist at Michigan State University (MSU), focused on insect ecology and behavior to develop insect pest management practices for sustainable crop production. Currently, Isaacs is leading a national project to develop sustainable crop pollination practices for specialty crops, involving four MSU programs and 15 institutions nationwide. He works through Extension programming to translate findings into real-world experiences, giving farmers access to best practices and quick resources. In addition, Isaacs serves on the Bee Better initiative’s advisory board.

Can you define pollination services?

The simple definition for pollination services is the value that wild bees provide to agriculture. When we’re thinking about pollination services, in general, it is always coming from wild bees. You can bring in honeybees and you’ll get the pollination services from those, but you are paying for that service. It is something you’ve invested in to manage your farm. We’re looking at the benefit to agriculture of the wild bees on the farm and helping move pollen back and forth, which many crops need to be fertilized.

What does it mean when we think about developing a farm that provides its own pollination services from native bees and pollinators?

In this scenario, you don’t see bee boxes, you don’t see a beekeeper and you don’t have the typical vision of buzzing hives on the farm. Instead, native bees need habitat in and around the farm. In the U.S., there are about 4,000 species of wild bees. Some bees nest in bushes, hollow stems or tree cavities, while many species nest in the soil. At the end of the day, native bees need diversely planted and undisturbed areas of land to be able to nest. Several native bee species don’t fly far, so you need a patchwork inclusion of habitat areas near crop fields so they can fly around 300 feet from their nest out to visit flowering plants.

Has there been any reaction to the practice of re-establishing bee populations as a solution to issues the bee industry is facing?

I originally got into pollination because I was interested in insects and what they were doing in the blueberry fields that I visited. I started doing this around the time when colony collapse disorder became a bigger issue. One of my biggest motivations is to help growers guarantee that they will get pollination each year. I see wild bees as a way to mitigate the potential risk that honeybees are prohibitively expensive or in the event they’re much more scarce. Native bee pollination can be seen as an insurance policy in some ways. For instance, what do you do on a day when your flowers are all open and it’s cool and honeybees are not well adapted to flying in those conditions? Or what do you do in a year where bloom happens much earlier and beekeepers are unable to get to you during the pollination window? I think as a farmer, it’s about trying to make sure that each year you get reliable pollination and aren’t losing out on potential yield because there was less pollination than you could have got.

How hard is it for a farmer “starting from scratch” to attract native bees and other pollinators back on to their land?

At the very start of things growers can be thinking about cover crops that will bloom and reward bees. There’s also just the simple act of not mowing some parts of your farm. Just some simple tweaks can help. We also have a lot of hedgerow opportunities for people to put in willow or maples or trees and shrubs that could not take up a whole lot of space, but could start getting some resources into the farm for bees and other beneficials.

Plus, I think this is where the Bee Better program will really help. It all starts with an evaluation of where you currently stand. Where do you have habitat that might be supportive for bees on your farm already? Are you using integrated pest management practices that allow you to minimize the risk of pesticide exposure to bees? Some changes can be quick while others will take years to establish.

Can you break down what one kind of native bee species needs to thrive?

For bumble bees, a mated queen who mated last fall spends her winter in the ground either in an old rodent burrow or some other nest under leaves and debris. When it warms up in the spring she starts getting active and will come out and start visiting some of the earliest flowers. She’ll start working flowers, but also trying to find a new nest site. Then they’ll start laying eggs and they’re bringing that protein and nectar back to the nest. They make a tiny little pot for honey but that’s just for their offspring. They’re not collecting large amounts of it.

Once those first eggs turn into larvae that turn into workers, so we’re a little bit later, probably into June by now. She now stays home and those workers that are being laid that spring, they start to forage and they’re out visiting the flowers and bringing back the resources. She’s still laying the eggs, but they’re bringing back the food for the colony.

How large does a colony typically get?

The common species around here will get to like 150 to 400, depending on how good they are and where they are located. Those bumble bees can also forage over a couple to five miles, so they’ve got a huge footprint potentially.

What kind of resources are needed to support a colony throughout the year?

Through the summer, the colony grows. For example, in late June in Michigan many of the worker bees will be out and will be contributing to blueberry pollination. Then that colony needs to persist from that early summer blueberry bloom all the way through to September to build up to its maximum potential. As daylight starts to shorten in the fall, and it cools down a little bit, that queen will switch from just making workers who were all sisters to making new queens and making males, the drones. Those queens will leave the colony, they’ll get mated, hopefully by a male from some other colony, and then that mated queen is looking for a place to spend the winter and settling down there. That’s how the cycle persists through the years.

That’s why it’s important to have places to nest because they’re going to need those in the spring and in the fall. That’s why it’s important that they have different flowers that bloom all the way through the season. The colony is really dependent on consistent intake of resources and increasing amounts of that as it grows through the summer.

What pitch are you making to growers to make them consider taking on establishing pollinator habitat on their farms?

I am fortunate that in the system I work in, we’ve got evidence that pollinator habitat plantings can increase both blueberry yield and benefit the biological control agents that will be moving into those fields to reduce pests. For instance, we did some work on a number of Michigan blueberry farms and demonstrated that the fields next to established pollinator-friendly plantings, over time, got higher abundances of wild bees. There were also a higher abundance of beneficial insects — think enemies of bad pests — in those fields.

The project lead, a graduate student, measured higher berry weights and found more egg predation on “bad” pests in the fields where the plantings were next door. We were able to convert the higher berry weight numbers into yield and then extrapolate that into expected increase in revenue per acre. It’s a relatively small increase, around 10 to 15 percent increase in the yield. However, because blueberries are a high net value crop, it ends up being a substantial increase in overall revenue for the farmer.

When you balance that against the cost of establishing the planting, we were able to show that within four or five years that producer would have made back their initial investment. I think putting all that together is where you help to tell a story about how there are a suite of benefits. It makes it even easier to help a grower see that this might be something that’s not just pretty flowers on the farm, but it’s of great economic and overall production benefit.

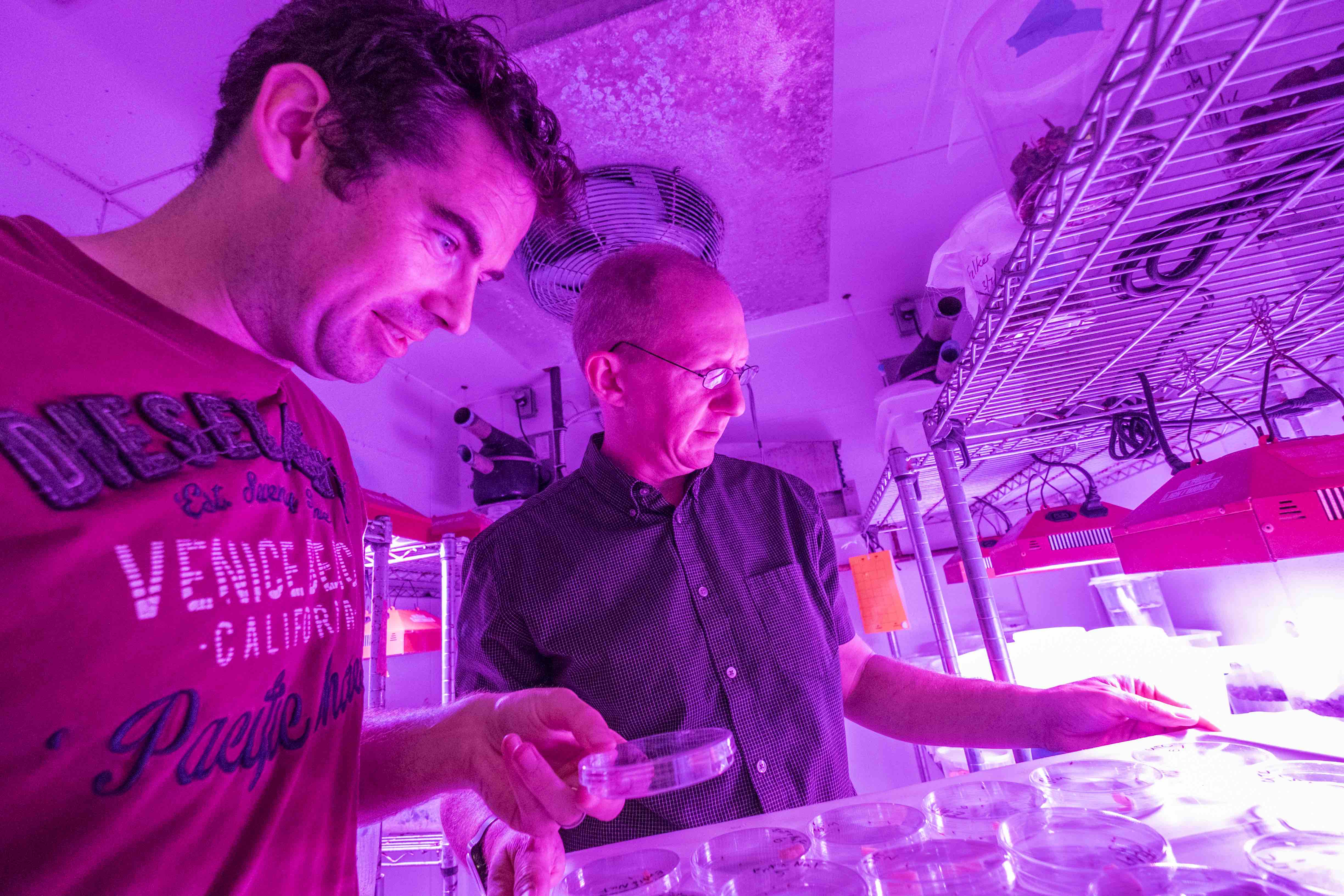

What do you love about your job?

It’s different every day. Everything from being in the lab to talking with farmers to working with students to doing research to traveling around to farms. I really like that I get to help people who produce food and get to know those farm communities. It’s a lot of fun to collaborate with them and the fact that they’re willing to let us come in and do some of our crazy research on their own land is great.