Organic food sales have been growing at a double-digit annual rate for the past several years, but growth in certified organic acreage has been much slower. With demand outpacing supply, imports of organic food products are rising dramatically and organic price premiums remain strong.

Despite higher costs of production and lower yields, Economic Research Service researchers found that organic price premiums more than outweighed any negative financial effects. During 2011-2014, they found that organic corn farmers netted $1.92-$2.27 more per bushel than conventional corn producers, and organic soybean farmers netted $6.62-$7.81 more per bushel than their conventional counterparts during the same period.

With organic production offering significant profit potential, why aren’t more farmers making the transition to organic?

The transition period itself appears to be a major stumbling block. Transition to organic certification requires a mandatory three-year period, when producers follow organic farming practices but are unable to earn a certified organic price premium. Concerns and uncertainty about the transition process discourage many farmers from attempting organic management or from following through with the transition to certification once begun.

Careful planning is a critical key to success for transitioning producers. Farm business planning helps farmers sort through alternative paths to certification, gives them the confidence to stay the course when unexpected problems arise and helps clarify communication with family members, neighbors, lenders and certifiers.

Effective planning begins with thoughtful identification and communication of the values that are motivating any transition to organic production practices. Next comes a thorough assessment of the history of the farm business as well as the physical, human and financial resources that characterize a farmer’s current situation. With values and resources in mind, farmers are well prepared to develop a financially focused transition strategy and crop rotation for their farms.

Types of transition strategies

In Tools for Transition project, Minnesota farmers tended to practice one of three transition strategies: whole, gradual or split transition. Organic transition is a long-term process, and a strategy that’s right for one farm might not work for another. The following examples highlight the distinct differences in the transition strategies used by Minnesota farmers.

Rory Beyer: Whole farm transition strategy

Some farmers, like dairy farmer Rory Beyer and his parents, transitioned their entire farm (crops and livestock) in a single three-year period. After Beyer returned home from college with an animal sciences degree, he began helping his parents operate their 600-acre dairy farm. Despite implementing significant herd genetic improvements, they struggled with volatile feed costs and low conventional milk prices. “We had been watching our [certified organic] neighbors…they were feeding their own grain, producing less milk and making more money,” Beyer explains. “So I started looking at what it cost us on a per cow basis to produce feed, buy feed and deliver it to our animals.”

After carefully budgeting out the costs, Beyer was able to make a strong financial case for the change, and the family decided to fully transition from conventional to organic during 2006-2009. Today, the Beyers belong to and market their milk through the Organic Valley co-op. Certification has allowed them to plan ahead and access improved financing terms due to price stability. “The thing that I’m the most proud of is making the decision to change,” says Beyer. “You don’t realize the impact the changes will have until after you’ve made them.”

Jonathan and Carolyn Olson: Gradual transition strategy

Veteran crop farmers Jonathan and Carolyn Olson transitioned gradually, one or two fields at a time, over nearly a decade. Between 2008 and 2013, the Olsons transitioned more than 1,100 acres of land from conventional to organic, beginning with just 40 acres. This measured strategy not only afforded the Olsons flexibility to work out the kinks in their new organic production practices but made conversion more palatable to their lender. “Our banker smiled when he saw the organic prices,” says Jonathan. “Gradually transitioning smaller acreages allowed us to learn,” he adds. “Fifteen years later, we’re still learning.”

Bryan and Theresa Kerkaert: Split operation transition strategy

The Kerkaerts maintain a split operation of 1,300 acres of corn, blue corn, soybeans, alfalfa and small grains. About 500 acres are certified organic and 800 acres are farmed conventionally. Because the Kerkaerts lease multiple parcels of land, some on one-year lease terms, it’s difficult to plan crop rotations or justify organic certification for all of their fields. “I don’t know if I’ll have that land next year, let alone five years from now,” Kerkaert explains. Split operations require rigorous attention to documented equipment cleaning, crop storage and commingling concerns, but for some farmers, it’s the right choice.

Crop rotation managment in transition

Among the farmers who participated in the Tools for Transition project, the choice of a transition rotation was influenced by two main factors:

- The need to build soil health and quality quickly, and get weeds under control. For instance, alfalfa is an attractive option in the Upper Midwest, though the establishment year can be challenging because hay yields are low and costs for seed and other inputs can be high.

- The desire to dedicate as much acreage as possible to the most profitable crop in the first year of certification. A first-year windfall supports the recovery of lost profits and increased costs incurred during transition.

Crop rotation decisions are impacted and dictated by location. Yield, cost ratios and market demand vary from region to region, impacting decisions at the farm level. For example, the below analysis of a sample crop rotation plan in southeast Minnesota is built on a strong local market demand for organic hay due to the proximity of many organic dairy farms. In addition, alfalfa hay is an appropriate choice for the region’s climate, helping build the soil during transition and suppressing weeds. Therefore, the owner plans to include alfalfa as part of the long-term organic crop rotation and will use alfalfa hay as a key crop during the transition period.

Effective crop-rotation planning requires good data, but data on farm performance during transition can be difficult to find. We used yield and cost ratios to summarize data collected from participating farms in the Tools for Transition project in order to create enterprise budgets — projections of the costs and returns of producing a crop — for transitional and certified crops based on a farm’s conventional enterprise data. Planning budgets can and should be based on careful analysis of farm records and conversations with other local farmers who have already gone through transition.

A sample crop rotation managment

Every transition to organic production is unique, but the following helps illustrate how a well-managed crop rotation during transition can affect net returns over an extended time period.

This example focuses on a 480-acre conventional corn-soybean farm in southeast Minnesota. Half the acreage is owned, half is rented, and the owner is considering a split transition strategy — transitioning only the owned land to certified organic production. The 240 acres of rented land will continue to be managed conventionally, with half planted in corn and half in soybeans.

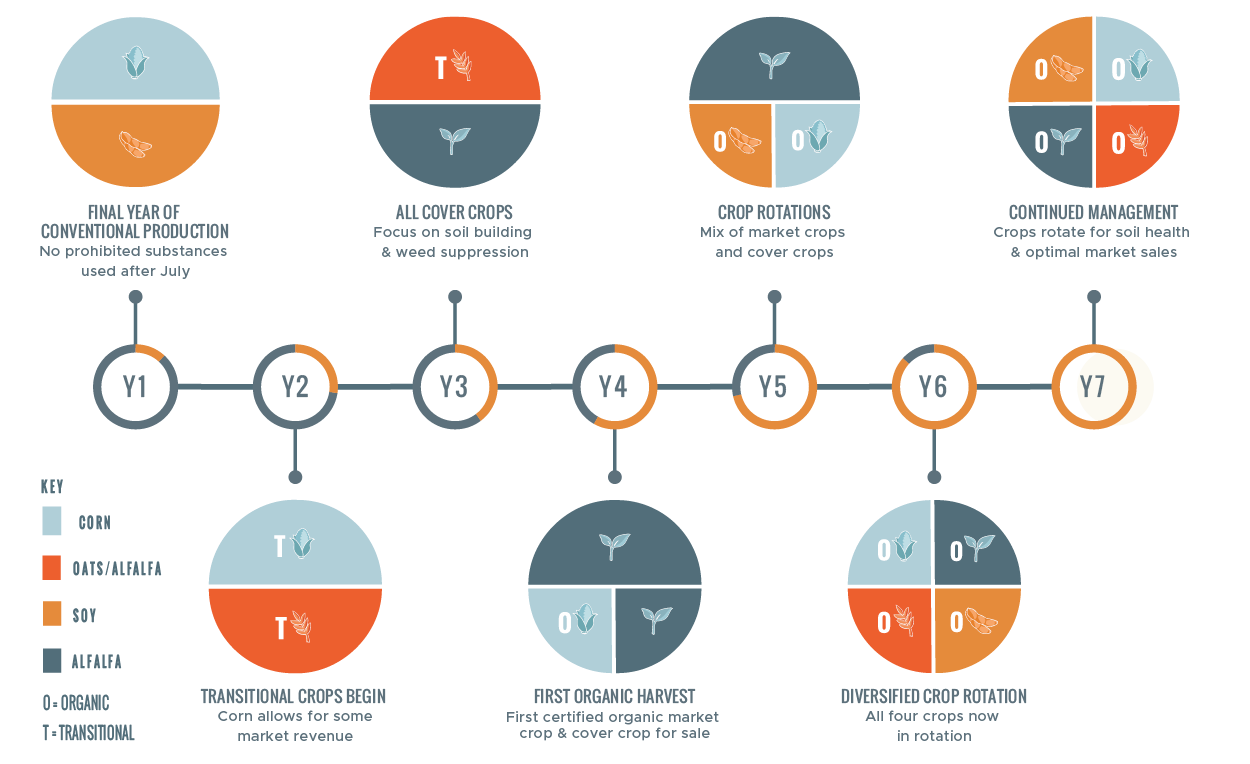

In this case, transition begins while the farm is still being farmed conventionally. Non-GMO corn and soybeans are planted on the owned acreage to be transitioned, and no prohibited substances — e.g., chemical fertilizers or herbicides — are applied after mid-July. This makes it possible to certify the land in year four prior to the harvest of oats, soybeans and corn.

In years two and three, half the transitioning land is planted in transitional oats under seeded with alfalfa each year. These two years are focused entirely on soil building and weed suppression, both critical for a successful transition to organic production. Revenues are low and costs are high during this establishment year, but the established alfalfa stand can be retained for another one or two years and generates positive net returns.

The transitioning land can be certified as organic in late July or early August of year four. A quarter is planted to corn and can be harvested as a certified organic crop. Corn is the most profitable organic crop in the Upper Midwest, boosting profits in the certification year. The first cuttings of alfalfa in year four will happen prior to the certification date, so it is still treated as a transitional crop for planning purposes.

Transition can be a financial roller coaster.

In the next three years, the long-term rotation is finally established. Organic corn is planted on land taken out of established alfalfa; organic soybeans are planted on land previously planted in organic corn; organic oats under-seeded with alfalfa are planted on land previously in organic soybeans; and established organic alfalfa fields stay in the rotation for a second year.

What does this all mean in terms of farm financial viability during transition?

In evaluating whole-farm net returns, it’s helpful to see fluctuations when comparing conventional, split operation and whole-farm transition operations.

Using our sample split-operation farm, after the last year of conventional production returns fall sharply at the start of transition and stay below the pre-transition level in the second year of transition due to reduced corn yield and very low returns for oats under seeded with alfalfa. The drop off in net returns under transition is even greater for a whole-farm transition. For some farmers, this drop off is simply too steep to risk any transition strategy.

However, the net returns for both of the transition strategies peak when the land is certified as organic (year four) and the crop mix includes organic corn and highly profitable established alfalfa. Returns fall slightly and then level off in later years once the long-term crop rotation has been established. Net returns in these years for the two transition strategies are nearly 40 and 90 percent above the conventional level.

It’s important to note that this example ignores yield and price risk, does not account for on-farm investments such as new equipment and may overstate returns in the first years after certification. These risks, along with the challenge of learning a new way of farming, need to be given careful consideration before anyone undertakes transition.

The key takeaways are that any farmer undertaking the proposed transition to organic production would need a strong balance sheet to weather the financial shortfalls of transition years and would want to work on strategies to account for lost revenues during transition through loans, conservation program funding with the Natural Resources Conservation Service or securing transitional premiums with potential buyers.

During the transition from conventional to organic management, small decisions can have big impacts — not only on the farm, but also for our larger agricultural landscape. One size does not fit all, and organic transition is not an all-or-nothing proposition. Real benefits can be unlocked by gradual or split transition strategies, and careful crop rotation planning can help farmers recoup losses incurred during the transitional years more quickly.

Being adequately prepared for the economic, agricultural and even cultural challenges of transition can help farms transition successfully to organic management, a model that can support long-term farm viability in the form of price premiums and price stability, while also reducing negative environmental impacts and improving soil health for future generations.