Principles are great. They guide our daily decisions, help us keep matters in perspective and encourage us to aspire to be better tomorrow than we are today. But adhering to them usually comes with a price.

In Marin County, Calif., Straus Family Dairy is working to align deep conservation principles with the economic realities of running a business. As the first organic dairy farm west of the Mississippi River, Straus’ goal is to show other farmers that undertaking environmental projects doesn’t have to hurt the bottom line.

“Everything we do has to make financial sense and has to have a payback so it can be replicated and be affordable for other farms to do,” said CEO Albert Straus.

One of the most important ways Straus Family Dairy is serving as a model is by demonstrating that conservation efforts don’t have to be cost centers. Some can save — or even make — money.

Ecosystem services

Discussions about the true cost of food often center on forces that keep consumer prices down by masking the hidden costs implicit in food production. But true-cost accounting can work in the opposite direction as well, and farms may have an opportunity to reduce their costs of production and generate additional revenue by cultivating non-food resources.

I want to make sure our farm is a model for a viable, sustainable farming business. And I want to show that it can be economically viable.

Those non-food resources can range widely, from the economic value of farms’ ability to attract agritourism to the generation of power through alternative energy installations. But cultivating ecosystem services requires infrastructure and labor, and those efforts cost money.

Today, farmers who pursue initiatives like on-farm wastewater management, carbon farming, the operation of methane digesters and other conservation efforts are faced with significant additional costs. In some cases, those costs can be partially offset with a combination of public grants and incentives, but many farmers still struggle to reconcile the intangible benefits of on-farm conservation efforts with the very tangible effects to their business’ bottom line.

Still, it isn’t far-fetched to think that someday farmers will cut costs or even make money from those efforts. Several organizations are working to establish frameworks, strategies and policies that strive to assign concrete, market-based pricing to a variety of ecosystem services. The strides they’re making have the potential to transform on-farm conservation from a mission-driven cost center to a positive contributor to the bottom line.

Straus Family Dairy: A case study

Straus Family Dairy has a long history of environmental stewardship. In the 1970s, Ellen Straus, Albert Straus’ mother, co-founded the Marin Agricultural Land Trust, the first agricultural land trust in the nation.

The Strauses stopped using herbicides and chemical fertilizers on their fields and transitioned to a no-till system for their pastures during the 1980s.

Then, in the early 1990s, Straus Family Dairy founded Straus Family Creamery, the first organic creamery in the nation. The move was driven by the grim realities of the commodity milk market, where pricing frequently failed to cover operating costs. By selling their milk in the organic sector, Albert hoped to access pricing that reflected the true costs of production, and develop a business that was sustainable from a financial as well as ecological perspective.

Methane digester

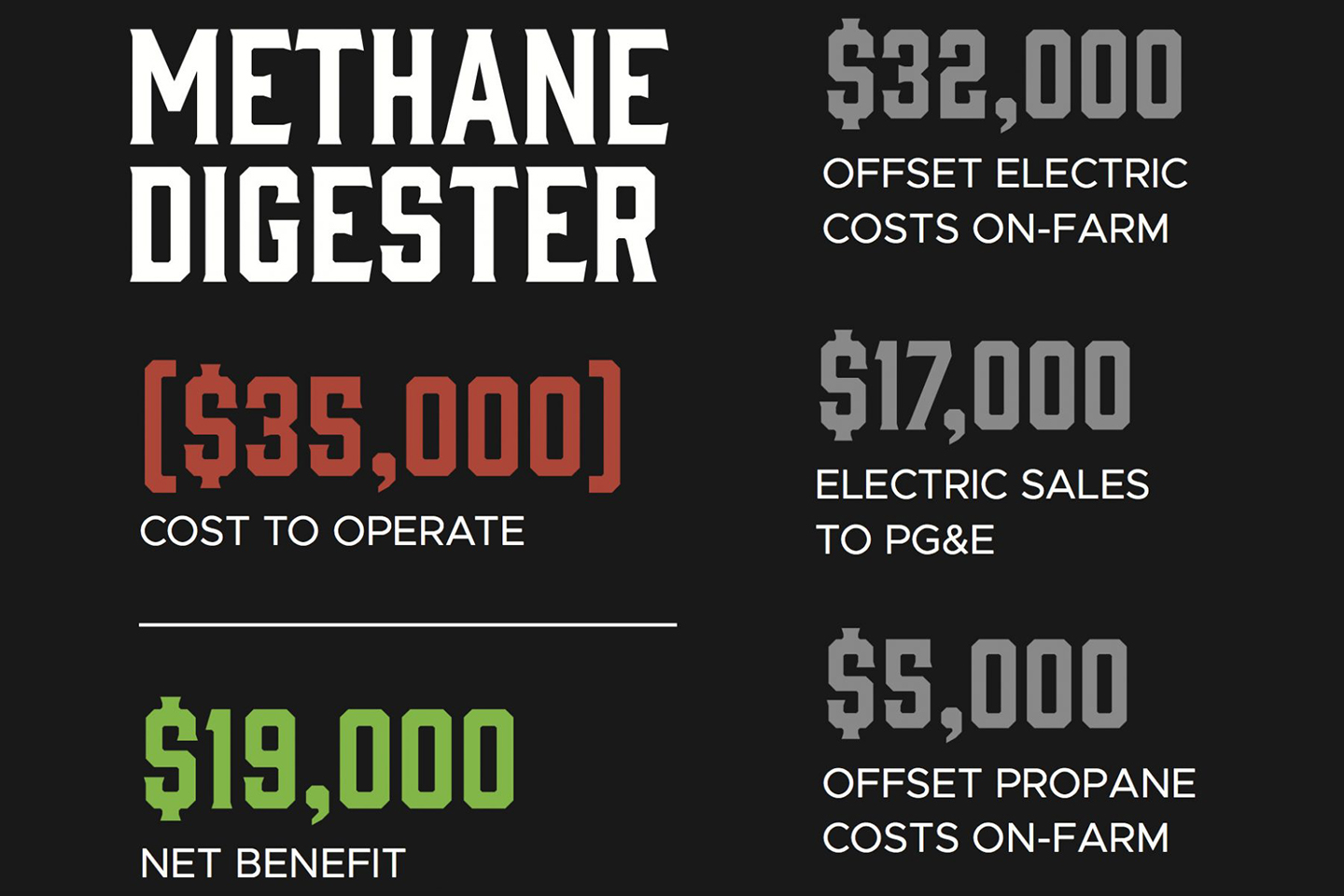

In 2004, Straus Family Dairy began operating a methane digester. By using a floating cover, the digester captures methane — one of the most potent greenhouse gasses — produced by decomposing cow manure and uses it to power a generator, creating electricity. Initially, the power was used to heat water for washing equipment; over time, Straus Family Dairy’s capacity grew to generate enough power to run the entire dairy and feed power back to the grid, to boot. Today, Straus Family Dairy’s methane digester captures and prevents the equivalent release of an additional 1,650 metric tons of carbon dioxide through methane destruction.

In addition to reducing the quantity of this potent greenhouse gas emitted by the dairy, the methane digester has an additional benefit: revenue. Albert estimates that the methane digester has an annual net benefit of $19,000 for Straus Family Dairy. This excludes additional value that has not yet been realized, including methane destruction credits as well as “potentially significant improvements in water quality.”

Building and operating a methane digester isn’t cheap.

“Most of the big concrete digesters have a very long payback,” said Albert Straus. “I did it very simply. It cost $355,000, of which we got $140,000 in grants. But that isn’t the norm. Having the farm outlay money to build digesters is going to be very challenging.”

To make it easier for other farmers to install and operate methane digesters, Straus Family Dairy is working on developing a public–private partnership to finance digesters that can be repaid over time with revenue generated by the sale of electricity.

Soil Carbon

About five years ago, Straus Family Dairy joined the Marin Carbon Project, a consortium of agricultural institutions, farmers, university researchers, county and federal agencies, and nonprofits dedicated to furthering the understanding of carbon sequestration in agricultural and rangeland soil. In 2013, Straus Family Dairy became one of the first three participants in a Marin Carbon Project carbon farming pilot program, and the only dairy to participate.

Carbon farming refers to a set of agricultural practices designed to pull atmospheric carbon from the environment and sequester it in soil by using the life processes of plants. Plants absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide during photosynthesis, and carbon molecules are used as building blocks to make root and leaf matter. As plant matter decomposes, its carbon becomes sequestered in the soil, which, in turn, builds soil health and adds organic matter, allowing it to support more robust plant life. By engaging in practices that help support this process, such as applying compost to pastures and rangelands, increasing vegetative coverage of soil and reducing activities like plowing, which cause soil carbon to be released into the atmosphere, farms may be able to sequester more carbon than they produce.

to not only power the farm, but to return electricity to the grid as well — all through its methane digester.Photo courtesy of Straus Family Creamery

The theory seems simple, but according to a paper published in the January 2013 issue of Ecological Applications, it could be extremely powerful. A single application of compost applied to half of the rangeland of California would offset 42 million metric tons of carbon dioxide — the entire annual energy use of California’s commercial and residential sectors.

The Marin Carbon Project helped Straus Family Dairy develop a 20-year Carbon Farm Plan, tailored to the dairy’s operations, that is expected to sequester about 2,000 metric tons of carbon each year. The plan includes initiatives to increase soil organic matter by applying compost to pastures, minimizing soil erosion by constructing windrows, increasing perennial native grass plantings in pasture and using planned rotational grazing. These initiatives are expected to sequester about 320 metric tons of carbon annually, or 20 percent of the total impact. The methane digester accounts for the remaining 80 percent of the carbon plan’s total sequestration.

After implementing these practices, Straus Family Dairy has started to see better yields in the pasture. “Over the decades, we were always adding manure as our fertilizer,” said Albert Straus. “But now, we’re able to see the correlation when we add compost and manure to the areas further away [that received less fertilization in years past], it increases the productivity of the crops and, at the same time, you’re sequestering more carbon.”

Carbon offset credits

Carbon farming also holds another tantalizing potential avenue for monetization: carbon offset credits. By building soil carbon resources, farms could qualify to sell carbon offset credits to polluters on the open market. Straus Family Dairy, like many other farms, has yet to successfully monetize its soil carbon resources in this way. But others have. Australia, for example, has established a robust carbon offset credit program that allows land managers to earn carbon credits and sell them to polluters.

A carbon market exists in the United States, but low prices remain a barrier. Torri Estrada, executive director of the Carbon Cycle Institute and a member of the Marin Carbon Project steering committee, says that California’s existing cap-and-trade program currently wants to keep prices below $10 a ton, which isn’t enough to pay for the practices farmers need to do to sequester carbon.

Estrada said one of the main barriers to monetizing carbon sequestration is that we’re trying to do it through existing energy markets, and we haven’t assigned an inherent value to carbon sequestered in soil. Only when markets start treating that sequestered carbon as a valuable resource will farmers be able to generate reliable revenue from it.

“In terms of value and public policy, [we need to] put a price on soil carbon,” said Estrada. “And if we do that, the farmer has a direct way to monetize it. We don’t give any value to farmers to produce that. There’s no price signal, and that’s the problem.”

Advocates are working on that area, with hopes that assigning financial value to these non-food agricultural resources will help farmers recoup the true costs of production, supporting family farm viability and the long-term health of the environment and economy.

For now, Straus Family Dairy is one of a handful of farmers showing that true-cost accounting doesn’t always have to mean rising prices. By leveraging on-farm resources, thinking creatively about waste products and accounting for savings realized by relying on ecosystem services over off-farm inputs, farmers can generate real value with the potential to offset other costs, or even decrease consumer prices over time. And that’s a possibility everyone can celebrate.