As the organic market expands, the cost to consumers is slowly but steadily dropping, making organic food somewhat more accessible to more people. This has been good news for wholesalers, processors and retailers. For farmers — and farm workers — not as much.

Why hasn’t the expansion of the organic food industry translated into higher wages and farm gate prices?

The simple answer is because organic farming is at the wrong end of the value chain.

But that is true for all farmers. What puts organic farming at a disadvantage is, in an organic nutshell, capitalism.

The high retail price of organic food frustrates farmers and consumers alike. Reasons given for the price difference between organic and conventional food — for some crops up to 300 percent–revolve around factors like low supply and high demand, greater labor input and postharvest handling, inefficient distribution chains and disadvantages in economy of scale.

All commodities — including food — are the products of human labor. Even honey, made by the planet’s beleaguered bees, needs to be collected and processed by human labor; wild mushrooms still need to be gathered; salt needs to be mined or produced in evaporating ponds; and wild fish must be caught. One way or another, the value of labor is embedded into everything we produce.

Organic systems use on average of 15 percent more labor than conventional farming systems. Sustainable organic farms provide a suite of valuable environmental services including soil, water and biodiversity conservation. Because of this — though it doesn’t translate into higher wages — the actual value of organic farm labor is much higher than the average wages paid for conventional labor. This is due to the extra skill required in organic farming and because conventional farming has set an artificially low level of “socially necessary labor time” in food production. Socially necessary labor time is a measure of the average level of worker productivity in a society. It determines how much labor is valued within a product. Here’s how it works:

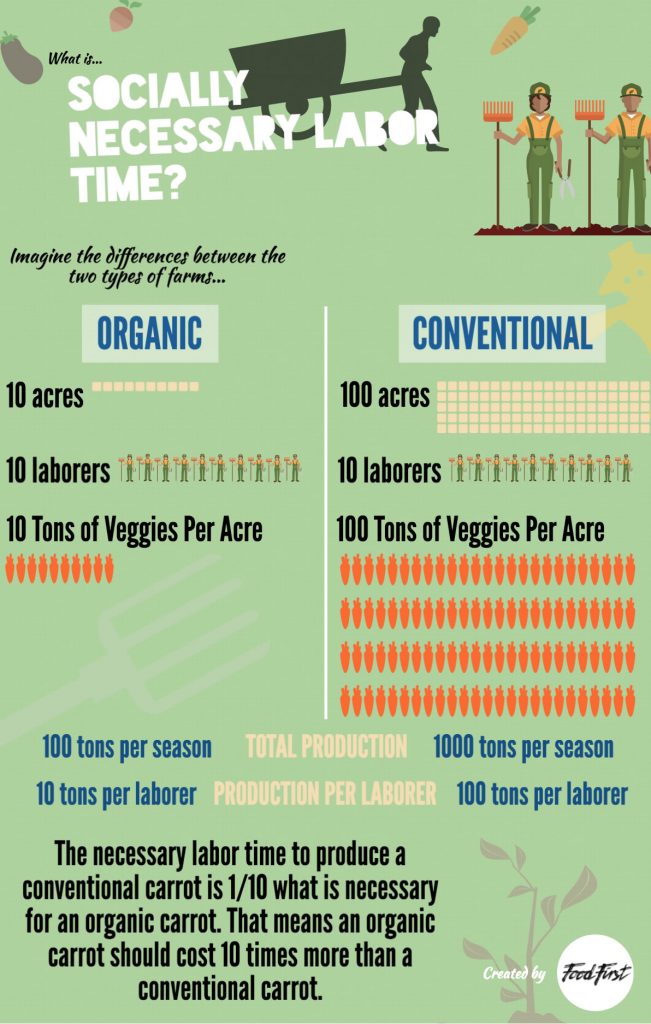

Imagine a typical 10-acre organic farm that grows vegetables 10 months out of the year and employs an average of 10 people. It produces 10 tons of vegetables per acre for a total of 100 tons per season. That means each person’s labor produces the equivalent of 10 T/yr., or a ton a month. So, each ton of produce “embodies” one month of a worker’s labor. Now imagine a neighboring 100-acre conventional farm also employing an average of 10 people over 10 months. Assuming yields are the same at 10T/acre (in the U.S. they are typically from nine to 20 percent more), total production is 1,000 tons/season. Each of these tons embodies just 1/10 of one month of a worker’s labor. So, the necessary labor time to produce, say a conventional carrot, is 1/10 what is necessary for an organic carrot. That means an organic carrot should be worth ten times more than a conventional carrot, just in labor costs.

Even though certified organic produce is often two or three times more expensive than conventional, by a straight-line labor calculation it should cost many times more, which it doesn’t. That’s because the value of labor embodied in the commodity — organic or conventional — is determined by average amount of labor time needed to produce that commodity. Because conventional agriculture dominates the market, it sets the labor standard. This is the “socially necessary labor time” for capitalist agriculture.

Once this value is established, other market factors can come into play, for example, supply and demand, input and transaction costs, organic premiums, conventional subsidies. Regardless, the main difference in price between the two is determined by the socially necessary labor time set by conventional agriculture.

When we understand food’s value (rather than price) the question, “Why is organic so expensive?” becomes, “Why isn’t organic more expensive?”

But that’s only half the story. Farm workers are also exploited in the food system, as evidenced by their abject poverty. The value of their labor is actually much higher than its cost in the labor marketplace. Why? Because the value of socially necessary labor depends on how much it costs to produce labor power in a society; how many years and resources it takes to raise and train, feed, clothe, house and maintain her or him, and the costs of health care and retirement. This is referred to as, “the cost of reproduction of labor.”

Undocumented workers — without whom the food system would collapse — are criminalized by definition. This status makes it extremely difficult for them to demand living wages, benefits or basic rights. Further, a significant part of the cost of undocumented labor is assumed by the immigrant’s countries of origin and are free to both Western Europe and the United States. The low cost of undocumented labor works like a tremendous subsidy to the food system. Most of this value is captured by shippers, processors, retailers and input suppliers. As a result, both farm labor and the family labor on organic farms are tremendously undervalued.

But, you say, an organic carrot is not the same product as a conventional carrot! The organic carrot has no pesticide residue, did not use synthetic fertilizers and did not poison people or the environment!

True, but the price of the extra labor power and the higher level of skill needed in organic production is not determined by the organic production process itself but by the cost of socially necessary labor in agriculture, generally.

This helps explain why it is often hard for small, organic farms to pay living wages and provide benefits to their workers. Many do, of course, but it is harder for them than for larger, conventional farms. It also helps explain a trend in organic farming to shift from small, diversified, labor and knowledge-intensive farms to large, capital-intensive, organic monocultures. These are the farms giant supermarket chains like Wal-Mart buy from because they can pay less for the product from these larger organic farms, and the product comes in familiar, standardized pallets on a fixed schedule.

The downward pressure of socially necessary labor time on wages also helps explain the growing conflict between small-and large-scale organic farms and between peasant farmers and new, mechanized farms producing ancient indigenous crops like quinoa for newer commodity markets. The combination of mechanization, large buyers and lack of regulations against environmental pollution by large-scale conventional production lowers the value of socially necessary labor and favors large, conventional farms.

Small-scale, organic family farmers tend to “self-exploit.” It’s not uncommon for them to make less hourly than the seasonal workers whom they hire. They may not be able to save much for their children’s education or their own retirement. It is in their objective interest to ally with farm workers to raise the minimum wage and improve working conditions on all farms —nlarge and small, organic and conventional, because this would raise the value of socially necessary labor in food commodities and the value of the farmer’s own labor. If all farm workers received living wages and basic social benefits, it would help to level the playing field between large-scale industrial operations and small-scale production, ultimately benefiting farms that use family labor.

There are many social and environmental benefits to certified organic and fairly produced products, including the possibility for small and medium-sized farmers — the ones upon whom both the organic and fair-trade systems were built — to get a better price. However, the steady entry of large-scale producers into these markets is driving down the value of socially necessary labor time. This is welcomed by large retailers because higher volumes mean more sales (and profits), it also lowers prices for the farmers and eventually squeezes out all but the largest producers.

From the perspective of value, there are different measures that could protect small and medium-sized producers. One is to peg the organic and fair-trade premiums to the costs of production rather than to the conventional price. Another is to internalize the environmental externalities of conventional production (a “polluter pays” principle for agriculture). Another would be for society to make housing, healthcare education and social services free to farm workers who work on diversified, organic farms, and to provide incentives for farmers to hire more year-round workers. This would raise the “social wage” to workers and help recognize the value of their work. If we continue to favor organic, sustainable and fairly produced food — and make large-scale chemical agriculture pay for the damage it does to people and the environment — eventually, organic will become the dominant system, re-setting the levels of socially necessary labor time.

The undervaluing of labor in food commodities is a heavy leveler and helps explain why organic and fair-trade products have failed to “raise the bar” in the mainstream food industry. When voting with our fork, we should remember that the freedom to buy food according to our values does not, in and of itself, change the power of conventionally produced commodities in our food system. If we want to change that, we have to change the way we value the labor in our food.