Lessons Learned: Biodiversity & Birds on Organic Farms

Biodiversity is an unsung hero protecting our agricultural future.

Certified organic agriculture identifies biodiversity as central to sustainable, long-term farming productivity. Organic standards protect and conserve landscapes, on the farm and nearby. Preservation of habitat for beneficial wildlife in the form of hedgerows and grasslands support natural pest controls. In short, organic agriculture promotes strong ecosystems on and off the farm in an effort to preserve the environmental services it depends on for success.

Unfortunately, many farming methods undervalue and threaten biodiversity with damaging practices. Use of non-discriminating farm practices can kill off or displace key agricultural partners, placing farms and wild habitats at great risk.

Birds serve as an indicator of good stewardship of natural resources. Most bird species are sensitive to environmental changes and are numerous enough for us to be able to observe their response to an event or change. For example, the number and type of birds present on a farm indicate overall quality of habitat such as food availability and opportunities for nesting. Learn more below.

Why does this matter?

Farms work in partnership with birds, enjoying increased pollination and pest control. In 1991, an article published on organic agriculture’s relationship with birds in the Journal of Pesticide Reform, cited how farms can be “rewarded by birds participation in the ‘pest management’ program[s]” and “provide insect control and eliminate the need for insecticide applications” in their role as on-farm pest managers.

And while we underestimate the benefits of birds in every day life, the National Audubon Society notes how birds are responsible for incredible impacts on farms from slowing the spread of disease and protecting against erosion. Here are a few examples from Audubon:

- The calculated value of birds’ pest-control actions for coffee farmers is as much as $125 per acre, or about one-eighth of the total crop value of $1,044 per acre.

- Ornithologist Julie Jedlicka put up nest boxes at two Northern California vineyards. With the approval of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, she simulated a pest outbreak, placing “sentinel prey” – e.g., larvae prey placed in the field to measure predator activity – between rows of grapes. The boxes attracted insect-eating birds, which in turn consumed 2.4 times more insects than in control plots with sentinel prey but no boxes.

- After every harvest, California’s rice farmers must get rid of a waste product called rice straw. Tilling the straw into the soil can be very expensive. Fortunately, farmers can benefit from wintering waterfowl foraging for grain, weeds, and bugs in flooded rice fields, which help decompose the straw. This could reduce the need for tillage, providing considerable savings to growers.

So, what can farmers do to increase on-farm biodiversity and support bird life?

Put into practice: Buffers and other non-cropped areas

Buffer areas or zones—also known as wildlife corridors, hedgerows, windbreaks, field borders and other non-cropped areas on farms—can provide critical habitat for birds. A buffer area may be required on organic farms to prevent contamination from substances prohibited under USDA organic regulations. But these zones and other non-cropped areas also provide excellent opportunities to plant and manage a buffer that can also benefit birds.

How to implement:

Field edges or other strips can be left idle and/or mowed at specific times of the year to provide additional cover and habitat. If mowed, waiting until late fall will help minimize the probability of disturbing active nests of ground nesting birds. You can apply the same practices to larger hay fields.

It is awfully hard to share the experience of an early morning on a farm.

Glittering specks of plants covered in dew. An endless sky of oranges, pinks, blues and grays. The joyful calls of birds, mixing for a powerful soundtrack of song.

The use and management of buffer areas to promote bird habitat requires attentive management practices to not only create, but also maintain healthful bird populations. But why does having birds on the farm even matter? Studies have shown that an increase in bird diversity—raptors, songbirds and other landbirds—provides an ecosystem service for pest removal and mitigation. These benefits can be brought to the farm by creating and maintaining buffer zones—an important and necessary tool for organic farmers meeting regulatory standards—that feature hedgerow “natural” habitat areas to entice desired bird populations.

Knowing how to choose the location, size and elements of a buffer zone hedgerow habitat can lead to successful increases in bird diversity and benefits for many farms.

Resources and references:

- Garfinkel, Megan, and Matthew Johnson. “Pest-removal Services Provided by Birds on Small Organic Farms in Northern California.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 211 (2015): 24-31.

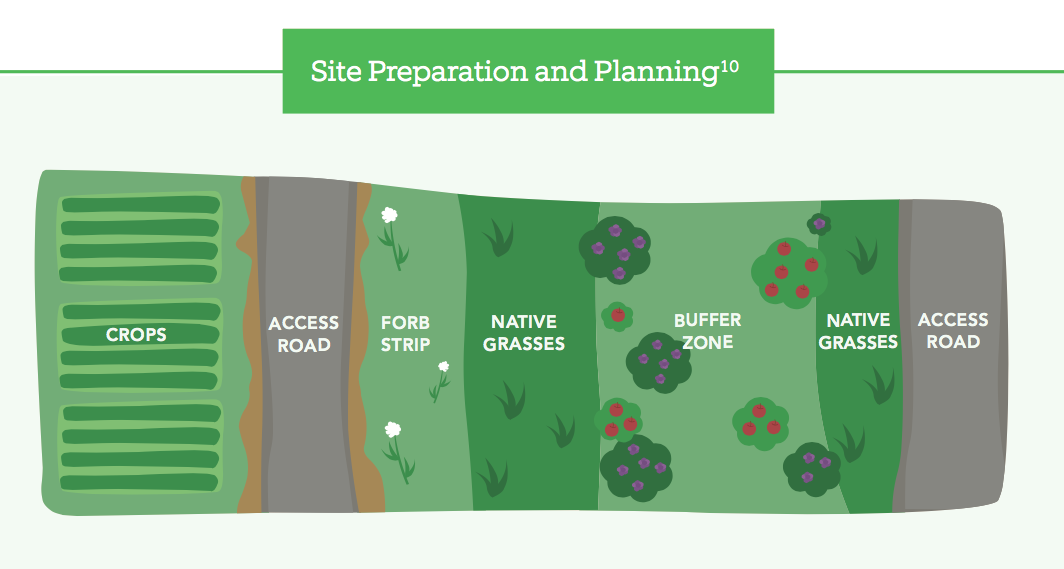

Site selection will be dictated by where the need is for a buffer area—non-cropped areas alongside roadways, neighboring field borders and agricultural drains—and accessibility for equipment and other management tools (irrigation, etc.).

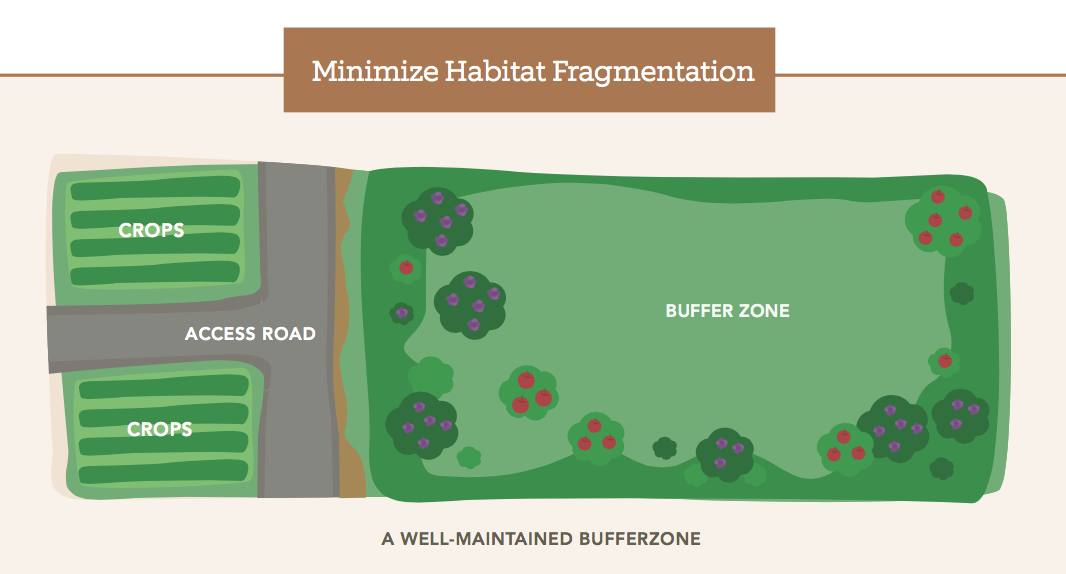

It is best to develop buffer areas that are continuous. A patchwork system of non-cropped areas as well as sudden linear edges from long, narrow rectangular blocks do not provide adequate diversity of habitat conditions. If and when possible, using irregular borders that are wide enough (30+ feet) to prevent predation. When buffers are fragmented, many ground birds and grassland birds are subjected to nest predation from crows, jays, skunks, raccoons, and others. Use of an irregularly edged and non-fragmented hedgerows—groups of trees, shrubs, perennial forbs, and grasses that are planted along roadways, fences, field edges or other non-cropped areas—combines need (ex. mitigate erosion and runoff) with bird-friendly habitat design. Researchers with UC Cooperative Extension and Audubon California, found that such hedgerow plantings tripled bird abundance and doubled bird species richness, but did not increase the bird abundance in the adjacent crops.

It cannot be stressed enough that a key component to a successful buffer on organic farms is site preparation. Be sure to learn about variations within buffer types and begin site prep at least one year in advance to minimize weeds whenever possible.

Resources and references:

- Conservation Buffers in Organic Systems: Western States Guide

- Hyde, Daria, and Suzan Campbell. Agricultural Practices That Conserve Grassland Birds. No. E3190. Michigan State University Extension, 2012.

- Earnshaw, Sam. Hedgerows for California Agriculture. Community Alliance with Family Farmers, 2004.

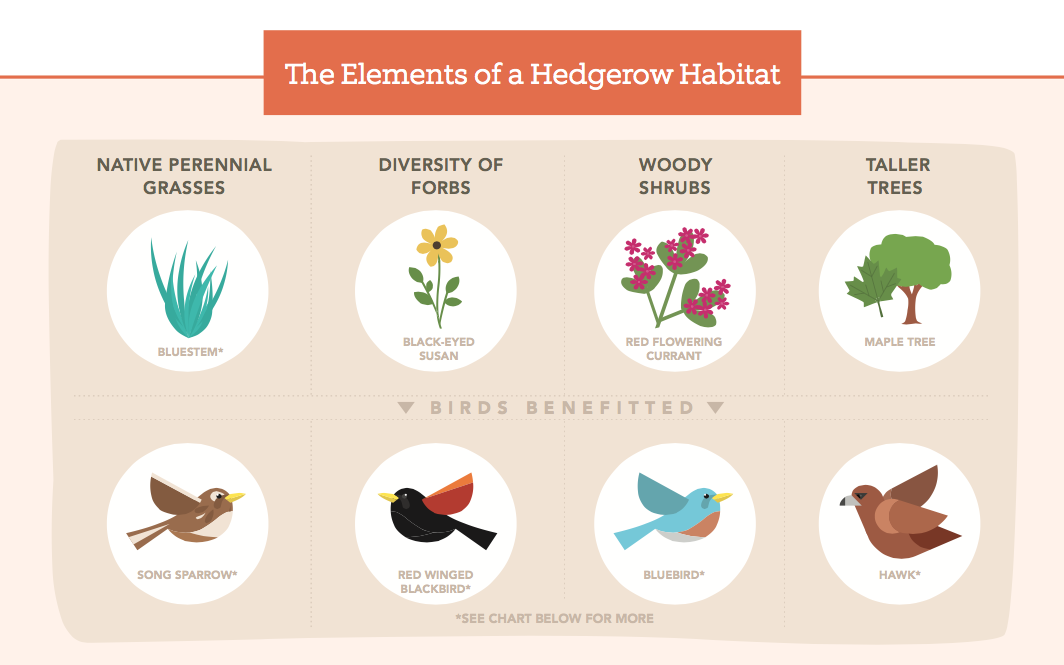

The right height, amount of residual vegetation, and grass/ forb combination is critical to establish a diversity of birds. Each species requires different vegetative structure and composition in order to construct a nest. The following basic elements of a native hedgerow habitat provides environmental structure and food sources for several bird species:

ENVIRONMENTAL STRUCTURE |

|

BIRDS BENEFITTED |

|

REGIONAL OPTIONS |

| Native perennial grasses Secure the soil through the establishment of a deep root system. Provides a place for several bird species for breeding, courtship, nesting, foraging, rearing young, and roosting. Allows for key habitat for birds to provide a valuable pest removal service on farms. |

Dickcissel, song sparrow, horned lark, upland sandpiper, eastern meadowlark, bobolink, and field/savannah sparrows | East: Indian grass, bluestems (big and little), switchgrass Midwest: bluestems, indiangrass, switchgrass, Eastern gamagrass West: bluestems, fescues, reedgrasses, needle grasses South: bluestems, Indiangrass, switchgrass, Eastern gamagrass |

||

| Diversity of forbs An assortment of forbs (herbaceous plants) will provide a steady source of nectar and pollen throughout the growing season. These non-woody flowering plants provide wildlife food and seed, attract insects to maintain ground and grassland birds and provide perches for songbirds. |

Dickcissel, red-winged blackbird, scissor-tailed flycatcher, kinglets, warblers, and other insectivores. | Regionally appropriate: Western ragweed, lambsquarters, black-eyed susan, blazing star, coreopsis, wild bergamot, flowering primrose, chicory and coneflower are examples of different regional native flowering forbs. |

||

| Woody shrubs Help create an important “transitional zone” along with food and cover for migratory and nesting birds. Food-bearing shrubs are critical to a large number of birds, especially during migration and provide protection from inclement weather. |

Robins, bluebirds, thrushes, catbirds, cardinals, waxwings, pine grosbeaks, finches, many others chickadees, starlings, hermit thrushes, American robins, cedar waxwings and northern mockingbirds. | Regionally appropriate: Buckthorn, hawthorn, red flowering currant, elderberry, black gooseberry, toyon, coffeeberry and tobacco brush are examples of of different regional native woody shrubs. |

||

| Taller trees Provide shade and reduce evapotranspiration, as well as create attractive nesting areas and perches for predatory raptors, a helpful addition to an integrated pest management strategy to control crop damaging rodents. |

Sharp-shinned hawks, cooper’s hawks, American kestrel, red-tailed hawks and barn owls. | Regionally appropriate: Native mast-producing trees such as hickory, chestnut, crabapple, walnut, sugar maple, beech, oak and dogwood provide habitat, food and protection. |

Resources and references:

- Garfinkel, Megan, and Matthew Johnson. “Pest-removal Services Provided by Birds on Small Organic Farms in Northern California.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 211 (2015): 24-31.

- “Hedgerows Turn Farm Edges into Bird Habitat.” Audubon California. 2015.

- Landscaping for Wildlife: Scrub-shrub Habitat and Hedgerows. Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey, 2012.

- Olson, Shilah, Karen Lamson, Mike Omeg, Brian Tuck, Susan Kerr, and Ellen Hammond. Attracting Birds of Prey for Rodent Control. EC1641. Oregon State University Extension Service, 2012.

A buffer zone hedgerow should be prepared for planting by a combination of disking and seedbed shaping for perennial grass and forb seed mix. The best bet to manage weeds later on is to avoid using a no-till drill on unworked ground. And whether using flat or raised beds (Long and Anderson recommend 60-inches), it is important to use plants that only tolerate flooding if the hedgerow will be flood-irrigated. Space large shrubs at 15-foot intervals and place smaller ones in between at 7.5-foot intervals. Trees need a 20- to 30-foot spacing, depending on the variety.

Plant native perennial grasses at 12 to 14 pounds per acre and the “forb strip” at 15 to 20 pounds per acre. It is best to use a no-till drill for the native grasses because the long awns on some varieties tend to get stuck in the drills. Alternatively, perennial grass seed can also be broadcast at 20 to 25 pounds per acre, and forms at 20 to 30 pounds per acre, then lightly harrowed by dragging a chain across the site to cover the seed.

The best time to plan is either in fall or early spring depending on your region, but when cooler and wetter conditions are in full effect to allow plants to establish well before summer heat sets in. Irrigation every 1 to 2 weeks for the first few years will help the plants become well rooted. Bird scare tape on poles can help with bird herbivory on new for seedlings until well established.

Resources and references:

- Long, Rachael, John Anderson. “Establishing Hedgerows on Farms in California.” ANR Publication 8390 (2010): 1-7.

Farmers must assess to determine which mowing practices they want to use while maintaining economic profitability. It’s important to note that if the hedgerow perennial grasses are to be harvested, cut or maintained, nesting birds do not react in time to avoid high-speed harvesters and will not flush at night. The following tips will help keep bird populations out of harms way when possible:

- Lower the mower speed, especially where birds have been observed.

- Avoid nighttime mowing.

Delay mowing

Depending on your region, it is helpful to know what birds are most likely to nest in the perennial grasses and/or forage in the outer edge of your hedgerow. Checking in with your local Audubon Society to find out species nesting dates and patterns and either preempt or delay maintenance by several weeks to avoid the nesting cycle.

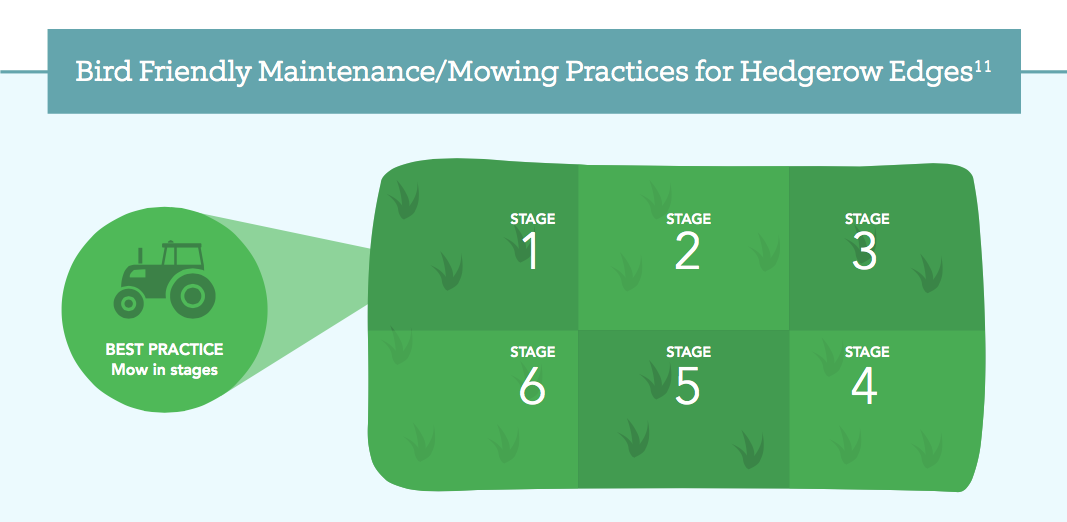

Use rotational mowing

Using a hayfield management approach of rotational mowing will allow hedgerow areas to be in various stages of growth and vegetative diversity throughout the year. It is helpful to identify areas not critical for early mowing or those that are usually too wet for early mowing. Simple avoidance of areas where birds are frequently seen or leaving small patches unmowed can protect many nesting birds and provide suitable cover and feeding areas for the rest of the summer.

Flush and daytime mow

A flushing bar is a simple tool that drags chains ahead of hay mowers to scare wildlife out of harms way. It is important to note that birds that are flushed will not be able to nest successfully in these areas but may be able to re-nest elsewhere, depending on the time of year. Attaching flushing bars to front end loaders using quick attach plates or fork pockets makes for an easy assembly process. One can design their own flushing bar or be specific to equipment by reviewing the www.theflushingbarproject.net and resources from the Minnesota NRCS.

Resources and references:

- Hyde, Daria, and Suzan Campbell. Agricultural Practices That Conserve Grassland Birds. No. E3190. Michigan State University Extension, 2012.

- The Flushing Bar Project, Minnesota NRCS

Put into practice: Long and diverse crop rotations

Small insects (invertebrates) are key for the growth and development of many bird species. It’s a simple formula: small insects = bird buffet. Varied crop rotations and the absence of most synthetic materials allow for more insects-as-food-source for birds. Rotations increase plant diversity and often increase the biomass of soil organisms, supporting larger populations of invertebrates. Longer and more diverse rotations provide more cover, habitat and nesting opportunities for many bird species.

How to implement:

Crop rotation is a core practice of organic farmers; rotations are required under USDA organic regulations to help enrich organic matter in soils, manage pests and control erosion. Producers can also plan and use crop rotations to benefit birds as well as other wildlife.

- In general, the best practice is to increase the diversity of a crop rotation by including as many different crops types – legumes, grasses and broadleaves – as manageable.

- The schedule and planting plans for rotations can ensure that some fields will always provide adequate food and cover for birds.

- At harvest time, leave a segment of the spent cover crop or stubble in the field for additional habitat.

- In addition, cover crops take on additional importance during non-crop times of the year. For example, cereal rye can provide nesting habitat for grassland birds and sorghum-sudangrass can provide food for songbirds.

Research:

- Girard, Judith; Mineau, Pierre; Fahrig, Lenore, (2014) “Higher Nestling Food Biomass in Organic than Conventional Soybean Fields in Eastern Ontario, Canada.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment

- Quinn, J.E., J. Brandle, R. Johnson. 2014. Identifying opportunities for conservation embedded in cropland anthromes. Landscape Ecology. 29(10):1811-1819.

- Quinn, J.E., A. Oden, J. Brandle. 2013. The influence of different cover types on American Robin nest success in organic agroecosystems. Sustainability. 5:3502-3512.

- Jones, G. A., & Sieving, K. E. (2006). Intercropping sunflower in organic vegetables to augment bird predators of arthropods. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 117(2), 171-177

Additional Resources:

Learn your local bird species

Adopting practices that address the habitat requirements of local bird species will maximize the impact of your conservation activities. In general, look for bird species that prefer open land or prairie habitat as they are more suited for agricultural landscapes. Additional bird species prefer nesting in hedges and forested areas within or adjacent to an agricultural landscape, as articulated in the above hedgerow buffer zone section.

Eastern US: Eastern meadowlark

Eastern meadowlarks find habitat in open fields, pastures and meadows. They can breed in hayfields and sometimes in other cropland, while overwintering in cultivated fields. Meadowlarks’ diet consists of insects during most of the year and seeds in the winter. The eastern meadowlark is in decline due to a loss of quality habitat. Learn more at Audubon Society.

Central US: Grasshopper sparrow

Grasshopper sparrows prefer tall grasses and weeds in grasslands, hayfields and prairies. Nests are built on the ground, well concealed at the base of weeds or grass. Sparrows feed mainly on insects including grasshoppers, but also eat weed and grass seeds. Populations are in decline and the grasshopper sparrow is considered a “priority bird” by the Audubon Society. Learn more at Audubon Society.

Western US: Burrowing owl

Burrowing owls prefer open ground with short grass and can be found in grassland and farmland. Nest sites are simple burrows in the ground often surrounded by bare soil or short grass. Their diet is comprised of insects and small mammals such as voles and mice. Populations of burrowing owls have been declining for many years due to habitat loss and are considered endangered or threatened in some areas. Learn more at Audubon Society.

Research:

- Quinn, John E; Brandle, James R.; Johnson, Ron J. (2012) “The Effects of Land Sparing and Wildlife-friendly Practices on Grassland Bird Abundance Within Organic Farms.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment

- Quinn, J.E., J. Brandle, R. Johnson. 2014. Identifying opportunities for conservation embedded in cropland anthromes. Landscape Ecology. 29(10):1811-1819.

- Fischer, C., Flohre, A., Clement, L.W., Batáry, P., Weisser, W.W., Tscharntke, T. & Thies, C. (2011) “Mixed effects of landscape structure and farming practice on bird diversity.” Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment

Additional Resources:

- USDA NOP Biodiversity and Natural Resources Guidance

- Wild Farm Alliance

Range of resources for farmers about increasing biodiversity - USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

Provides a wide range of financial and technical support for producers to implement conservation practices, including wildlife habitat establishment - Environmental Benefits of Organic Agriculture: Biodiversity Webinar

Dr. John Quinn, Assistant Professor of Biology at Furman University presents a webinar that describes how organic systems enhance biodiversity at several levels. - The Audubon Society

- Oregon Tilth Big Questions, Answered: Buffer Zones

- Organic Farmer’s Guide to the Conservation Reserve Program: Field Border Buffer Initiative

- National Organic Farming Handbook

The handbook describes organic systems and identifies key resources to guide conservation planning and implementation on organic farms.

Acknowledgements:

- Special thanks to John Quinn, Assistant Professor of Biology at Furman University for his support in developing the content for this edition of Lessons Learned.