The organic carrots that a group of farm workers has just pulled from the sandy soil of a farm in the most northern part of Germany, close to the Danish border, look perfect: long, deep orange in color and with the slightly floppy, glossy greens still attached. It takes the men seconds to gather them in a bunch and tie them, ready to go through the washer. This year’s carrots are sweet, deep in flavor and very much in demand, says farmer Heinz-Peter Christiansen, but whether the distributor will give him a good price remains to be seen.

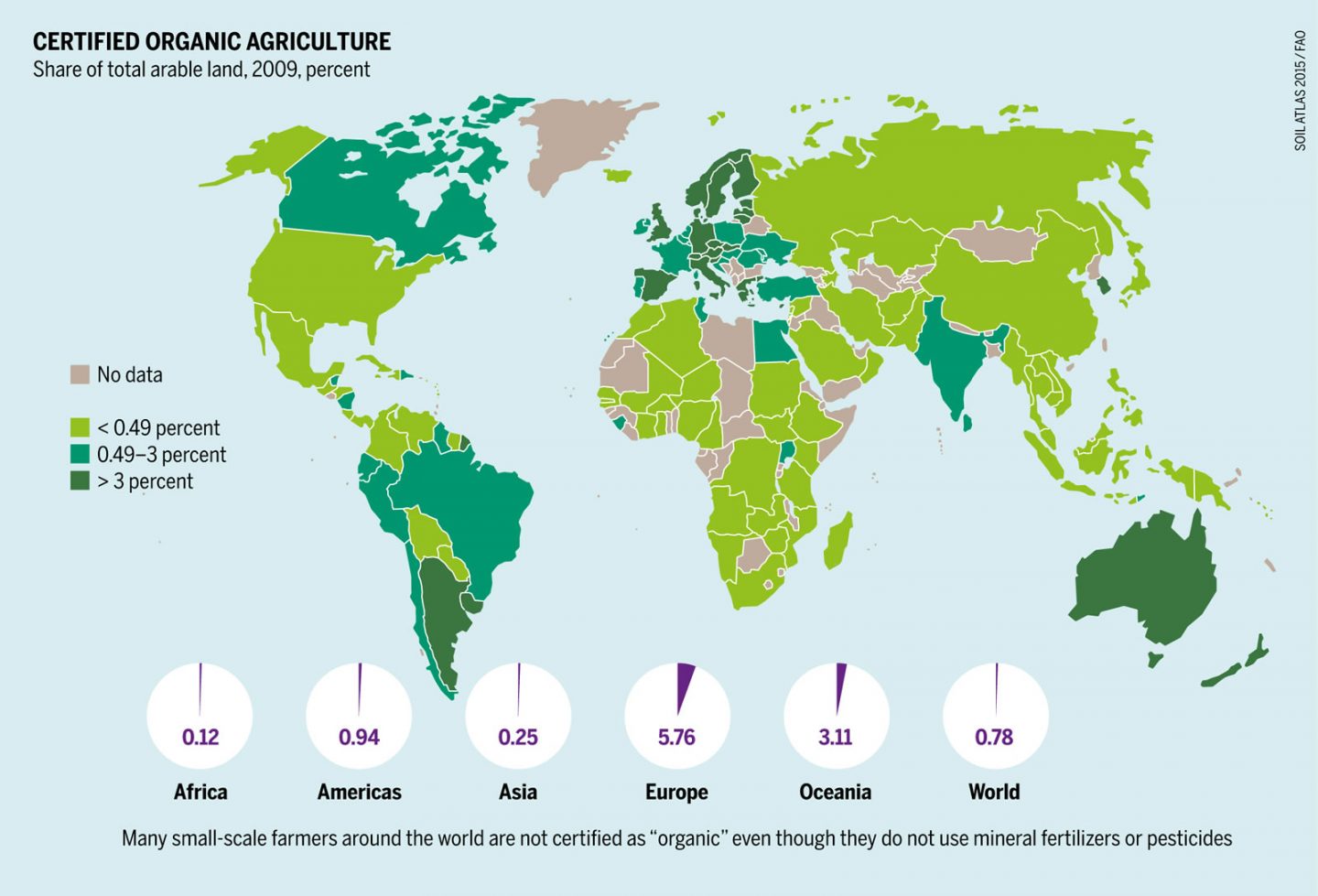

Organic farmers across Europe have similar worries. Consumer demand for organic produce has been increasing year on year, often in double digits. Organic agriculture has grown steadily; today a third of the world’s organically managed farmland is in Europe. But when it comes to prices, supermarkets in particular, expect immaculate organic produce to cost no more than conventionally produced fruit and vegetables.

A mottled picture

The organic market looks very different across Europe; it’s split into consumer and producer countries. Consumption is particularly high (and growing) in western European countries, in Germany and France, but also in Benelux and in Scandinavian countries. The highest percentage of land under organic cultivation can be found in Italy, Spain, and of late, in eastern European countries like Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania. But things are in flux: Italians love their food, they look for quality and taste, says Jean-Pierre Bringiers from the organic seed company Sativa. That’s why more and more Italians buy organic, in particular wheat products like pasta. Since 2012, the organic market in Italy has grown between 13-15 percent each year, says Bringiers, despite the country’s severe economic problems.

Trailblazer: Austria

With 20 percent of organic consumption and 20 percent of land under organic management, Austria is a poster child of the organic movement in Europe. Things got going in the early ’80s, when the owner of the country’s largest supermarket chain started stocking organic produce which proved increasingly popular. A few years later, the government began subsidizing organic agriculture. “We are a mountainous state,” says Christine Jasch, expert on social standards and auditing, “Eighty percent of the agricultural land is unsuitable for industrial style farming.” For a lot of farmers, going organic was the only way to survive and by now a lot of Austrians are proud of their organic farmers who protect the environment, produce delicious food and improve Austria’s image beyond its borders. Like many European countries Austria has its own organic label which sits next to the EU organic label. Since 2010, producers of packaged organic food have been required by law to use the leaf-shaped EU organic label and display the code number of the certification organization. In different countries, consumers will find a host of different organic labels guaranteeing an even stricter organic production standard, for example, the Demeter logo for biodynamic produce.

Political factors

Continuously growing consumer demand and an EU standard for organic production — it might not have happened if all European countries had political systems like the U.S. and Britain, which makes coalition governments unlikely if not impossible. In Germany in 1980, a bunch of mostly muesli munchers concerned about nuclear waste, acid rain, animal welfare and pesticides in their food founded the Green party.

Three years later the first Green MPs were elected. Since then, the party has frequently been the junior partner in coalition governments on federal and state levels. There are similar movements and parties in most other western European countries. Why does it matter? Politicians shape policies and Green politicians root for organic.

“Organic farming must become the prevailing standard for agriculture,” says Christian Meyer, minister for agriculture in Lower Saxony, one of seven state-level Green Ag-secretaries in Germany. Of course everything in Europe is a lot smaller compared to the States: Lower Saxony is as big as New Hampshire and Vermont put together and its population is twice that of Oregon. In regard to agriculture, Lower Saxony is Germany’s Iowa with nine million hogs, mostly in factory farms, almost 90 million chicken (broiler chicken and laying hens) and an increasing acreage of corn grown for feed and renewable fuel.

Forty-year old Christian Meyer wears neither beard nor sandals, and his most exotic piece of clothing may be the beekeeper’s hat which he needs when he is checking the two hives in the ministerial garden. When Meyer took office in February 2013, he was committed to promoting organic agriculture. “Industrial agriculture is bad for the environment,” he says, “we know that nitrate levels in the groundwater are far too high, pesticides are killing pollinators, in particular bees, it’s just not sustainable.” He has increased subsidies for organic farms; no other state pays more. It helps to keep organic farmers to stay on their land and others to think about conversion, but the acreage under organic management still is a lowly three percent, (the German average is six percent.) “Land prices are extremely high,” says Meyer. Even generous state government subsidies can’t match what the renewable fuel lobby is willing to pay for extra corn acres.

Level field for organic

“Conventional producers have to pay for the follow-up costs of their way of farming,” says Christian Meyer. Since he’s come to office, hog farmers have had to install filters to improve air quality, and animal welfare standards have been tightened. Meyer has chosen a carrot and stick approach —farmers get a premium for hogs whose tails have not been cut or bitten off. And chicken beak trimming will become illegal at the end of 2016, even though as a result the cost of an egg will go up by three cents, narrowing the price difference between conventional and organic eggs. Consumers care about animal welfare even if it comes at a price — and supermarkets nationwide have reacted by announcing that producers will have to comply with Lower Saxony’s egg-production standard in the future. Other European countries will introduce similar legislation.

But Christian Meyer is working toward a complete change of the entire agricultural system. One step towards that is reliable support for organic farms which at the EU level is missing at present. The European Organic Regulation is under review and that creates a lot of insecurity among organic farmers and those who think about conversion, says Meyer. So far, he says, neither the federal government nor the EU are committed to organic agriculture, “They all still cling to the old ‘get bigger or get out’ mantra,” says Meyer, “and ag-lobbyists do all they can to keep it that way.”

Shoppers are increasingly looking for quality and taste in food and organic agriculture delivers.

Lower Saxony finances organic research, a school fruit and veg program that is 80 percent organic, more than 100 additional staff have been hired to ensure compliance with organic and animal welfare standards, and district attorneys have a mandate to rigorously enforce the law. There are leaflets explaining the benefits of organic agriculture and how to find out about organic suppliers in your area, from CSA schemes to farmers markets and specialist shops selling only organic goods, both food and non-food. Meyer says consumer attitudes have been changing considerably across Europe. Shoppers are increasingly looking for quality and taste in food, and organic agriculture delivers. Reports about food waste have led some to unexpected conclusions: cheap food gets wasted more easily, it’s just not worth much.

Organic & local

Those who have closely watched the European organic market develop over the years worry that it’s fast becoming a two-tier system: with industrial style production of huge volumes of organic produce for large retailers vs. organic family farms struggling to survive through CSA schemes and direct sales. Jean-Pierre Bringiers from the organic seed company Sativa believes that in five to 10 years demand will outstrip supply. He sees the development as an opportunity because small, dedicated organic retailers and processors are starting to build relationships with organic producers based on longer-term supply contracts and fair pricing.

Lower Saxony’s agricultural secretary says small and medium enterprises are best suited for local organic food production — to him agriculture has to be organic and local to be truly sustainable. In Lower Saxony, small and medium size organic farms get higher subsidies than big, industrial outfits. And that’s where Christian Meyer starts dreaming big: if it were up to him, the billions the EU pays out in farm subsidies would go in future only to those who farm in an environmentally sustainable manner.